By: Simon Chanezon, Dimitry Karavaikin, and Katerina Stefanescu

Also, many thanks to Agata Zbij (University of Oslo) for providing information, insight, explanation and translation of a lot of the first-hand material in Norwegian.

Introduction National governments usually have trouble regulating and solving issues on a community level. This is especially the case in large countries where the diversity of environments creates a diversity of issues, especially ones related to climate change. For example, Spain’s climate varies depending on where you are in the country, and thus the will be inequalities in the effect of climate change on populations of a same country. A simple answer to this problem is community organization, especially in the form of city governments. For a diverse array of problems, a diverse array of solutions is needed, which is a breadth that a national government simply cannot cover. The solutions need to come from the localities themselves. Our problem is that a city’s scope of actions is limited. We believe that making inroads into solving climate challenges on a city-by-city basis is better than approaching the larger, overwhelming problem of climate change and having little impact. There may be scope to implement highly detailed, well-researched policies in major European cities and upon success branch out to other smaller cities. The question to ask ourselves, therefore, is whether the European Union can act to support local governments in the same way it supports national ones, and when it falls short, what international cooperation can be observed between European climate-minded cities? What lessons can we take from countries working individually to successfully set and tackle climate change policy?

European Covenant of Mayors The hardest part in answering this question is a problem that applies to all those interested in climate policy: how do we measure the actual impact of decisions and organizations? Words are said, objectives are set and then promises are broken. Multiple European organizations exist, and our role will be to judge their effectiveness in supporting localities in their efforts to fight climate change. We’ll be looking specifically at a main actor in European cooperation on city-wide climate policy: the European Covenant of Mayors.

The European Covenant of Mayors was launched in 2008 after the EU’s Climate and Energy Package was adopted. It has three main goals: help cities set objectives for themselves, evaluate their progress and provide a platform for the sharing of individual strategies. Theoretically it should push any mayor signing it in a greener direction and help the local administrations adopt efficient policies to get there. Let us judge the effectiveness of each component.

Objective-setting has become a repeating trend in international climate action. Failing to reach said objectives has also been a motif, with very few countries reaching their set objectives in the 1997 Kyoto Protocol and the US not even signing the document. Since then, much progress has been made especially since the 2015 Paris Climate Agreements, yet it is clear that while objective-setting is helpful in elaborating strategies, actual policies are needed. The Covenant of Mayors has “Action Plans”, which translates to said agenda-setting, thus inscribing itself in a long tradition of international climate action while, as we will see, taking a new, more constructive and binding approach.

One of the key components of the Covenant of Mayors are the progress reports which are due every two years. This is a way of evaluating how much closer the cities are to meeting their objectives (which are set for 2020 and 2030, thus keeping deadlines short). For example, the Italian commune of Aviano published a report in 2016 in which the following details are shown:

We can clearly see here that while more work is needed in the municipal building equipment facilities and transport sectors, half of the desired progress in public lighting has been attained. That “clearly” is of the utmost important because measuring progress can get so technical that most people without degrees in statistical analysis won’t understand the results. Having a working user interface open to the general public creates a very important sense of accountability for public officials. A caveat in this system is the large holes in the data that exist for some smaller municipalities, since more importance and attention is given to the large cities. However, the “role model” theory (according to which efforts made by large metropoles will be mirrored in their neighboring towns and communities) could provide a solution to this problem, the argument being that as long as cities like Berlin or Milan publish their progress, there will be pressure on the smaller nearby localities to emulate their “big brother’s” efforts.

Finally, we have what is maybe the most helpful section of the Covenant of Mayors, which is the “Good Practices” forum for exchanging solutions. This is a way for cities to share their most successful policies and ideas, under the basic assumption that there is possibility for cross-application. For an example we found the “Mur|Mur” strategy adopted by the French city of Grenoble, described as “Significantly improve the insulation and comfort of private condominiums built in the agglomeration between 1945 and 1975”. The short information sheet describing the policy is shown below, with links to more details on the Covenant’s website.

This strategy could be adapted by many other European cities suffering from the same problem of old uninsulated condos, with a precise description of how to best implement it. It is important to note, however, that since roughly 2012 not many strategies have been posted, and the energy put in the project seems to be decreasing, so maybe a new format or accord could re-dynamize cooperation.

The European Covenant of Mayors seems therefore to be an effective means of setting objectives and helping European cities attain them through a platform facilitating transparency and the exchange of solutions. However, because of it dating from 2008, it seems to be losing steam and a new agreement could bring back attention and effort to the cause of local climate action.

Case Study: Paris Paris since the election of left-wing mayor Anne Hidalgo is now arguably the most intensive site of French climate action, with the mayor starting an array of programs designed to make Paris clean, such as the vehicle-free day that happens every year now. Since the first day of that type in September 2015, the idea has become a Parisian tradition, reducing emissions by 40% every time. Since there are 6,000 deaths by pollution every year in the city, action was clearly needed. Additionally, the “auto-lib” and “vélib” programs have been greatly expanded: every couple blocks you can now find an electric car or a bike to rent. Again, these measure have become part of Parisian city culture, with high levels of use despite initial doubts concerning the theft of the bikes. Since then, major European cities like Cordoba (Spain) or Vienna (Austria) have adopted the program. This is an example of how sharing policies and ideas on a European scale can make climate policy-making more efficient. Expansive (and expensive) new train lines are being also being built to form interconnections within the greater Paris area, effectively reducing transportation emissions as well as (hopefully) unifying the city’s social classes.

Case Study: Norway

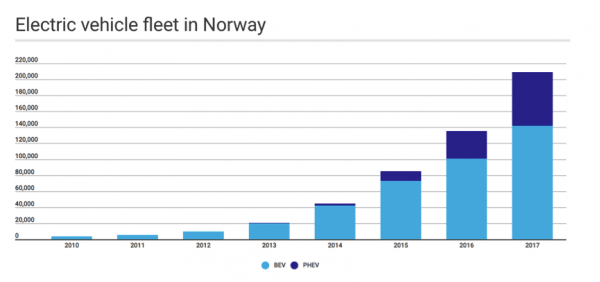

Source: EVS30 Symposium Stuttgart, Germany, October 9 – 11, 2017 , “Charging infrastructure experiences in Norway – the world’s most advanced EV market”, Erik Lorentzen, Petter Haugneland, Christina Bu, Espen Hauge

In general under the Norwegian model, policies focus on reducing the number of internal combustion and diesel engines on the road. The Norwegians use several policies to ensure this including “bomstasjoner” (urban toll points) to regulate traffic. Some cities, such as Oslo, adjust the rates charged at these toll points during rush hours if pollution levels increase too much. All electric vehicles are exempt from paying at these toll points, which is just one of the many incentives created to encourage electrification. Norway allows EV’s access to bus lanes, exempts them from road tax and has managed to quickly provide a robust network of charging stations.

The Norwegian model has had several key obstacles to being successful. Firstly, people have protested the urban toll system. Secondly, as with any electrification of a vehicle fleet, there are frequently cited global limitations on materials for lithium battery production and availability of charging terminals for electric vehicles. Thirdly, in general there has previously been pushback on adoption of electric vehicles based on other personal preferences. Fourthly, there were some worries about the ability of the electricity grid to cope with higher demand due to charging terminal usage. Despite these constraints, it seems that Norway has managed to drastically change the composition of the cars on their roads, even in a relatively short amount of time. The latest figures suggest that electric vehicles have hit an unprecedented level of capturing 52% market share in Norway.

Funding gained from bomstasjoner specifically has been spent on infrastructure projects and strengthening public transport in cities.

Could this be applied to other countries?

The key worries would be whether other countries that need this kind of drastic change would actually be able to fund it. The Norwegian model of shifting to cleaner road transport required heavy subsidization of electric vehicles in order to make the shift possible, subsidies which are now actually being rolled back. Just the schemes to build charging infrastructure cost NOK 50 mln. Other countries appear to face similar or even higher costs if they were to facilitate an increase in electric car adoption on a similar scale based on the current infrastructure and numbers of cars on the road (Norway has a relatively small car fleet overall). While Norway is able to provide these generous incentives because of its lucrative offshore oil industry, other countries could struggle to find funds for this. Furthermore, Norway’s energy mix is relatively favourable, with most (over 95% of) electricity being produced by hydroelectric power. Moreover, Norway has been setting itself non-binding goals (e.g. that by 2025 all cars on the road should be zero-emissions) – it is questionable whether these are consistently attainable and would work across all countries, and we already know how well many semi-binding climate goals have worked in the past. Also, while the electricity grid situation has been handled intelligently and in an organized manner in Norway, the same may not be true of other countries even if the energy mix were to become clean enough to make the shift worthwhile.

However, having said this, in Europe transportation accounts for a quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions, so there is much to be admired about Norway’s head on strategy.

Case study: Barcelona With urbanization on the rise globally, there has been a significant upward trend in the environmental costs associated with urban development. Air pollution, traffic, and the creation of heat islands are some of the most detrimental effects. This means that cities globally need to address these problems. In the face of these environmental concerns, smart cities and communities have turned toward innovation. One such example of this innovation is evident in Barcelona’s city planning. Through the introduction of superblocks, Barcelona is at the forefront of environmental progress.

Superblocks, also known as superilles in Catalan, provide “citizen spaces” for Barcelona’s residents by merging blocks together into car-free areas. These car-free areas provide an improved and more efficient mobility plan for the city. With the advent of superblocks comes reduced traffic and freed up space for people to walk as opposed to use motorized vehicles. Specifically, in Barcelona’s superblocks, traffic is reduced by 21%, a noteworthy amount considering the negative effects of traffic on the environment. Creating these open spaces has reduced noise pollution associated with traffic as well as emissions from vehicles. Currently, 61% of citizens live in areas with noise levels that exceed those considered safe and healthy by legislation. The implementation of superblocks has, thus, improved living conditions for many residents in the urban center.

By freeing up 60% of Barcelona’s streets, superblocks have actually improved quality of life and health of residents. Prior to the introduction of superblocks in Gracia in 1987, 3,500 deaths annually were caused by air pollution in Barcelona. Moreover, a study conducted by the local Environmental Epidemiology Agency concluded that approximately 1,200 deaths annually could be prevented simply by reaching EU-mandated nitrogen dioxide levels. In reducing air pollution via reduced traffic, superblocks are improving health conditions for Barcelona’s residents. With many residents suffering from asthma and other diseases that are exacerbated by atmospheric pollution, superblocks provide a beneficial service. Road accidents are also cited as another major health risk that is reduced due to superblocks.

Roughly 7 of the 13.8 million square meters of Barcelona’s streets are freed up due to superblocks. With such a significant portion of the city now solely intended for pedestrians, there has been a shift in economic practices. Open areas for people to stroll through enable the proliferation of street businesses. This economic incentive is met with a potential increase in community cohesion. Because the proposed superblocks that will first be implemented in the Eixample neighborhood of Barcelona are limited to spaces of 400 square meters, community ties will be deepened for the 5,000 to 6,000 residents of the superblock. While cutting off some ease of transportation and communication, the superblocks more than make up for this in economic and social benefits.

Other urban hubs can learn from Barcelona’s tactical urbanism as they try to implement similar means of environmental progress. Larger cities with greater populations of pedestrians such as Paris and Rome should look to Barcelona as a source of inspiration. They, too, can implement superblocks as a way to reduce traffic and pollution while improving health standards and community ties, an implementation which could be facilitated by the integration of the superblock strategy into the Covenant of Mayors Nations across the EU are in the position to employ such strategies and develop new ones as they move toward meeting their goals for environmental protection and safety.

To conclude, the EU provides some degree of support through platforms like the covenant of mayors, which help to set objectives, monitor progress and establish a platform for the exchange of ideas and solutions to climate change. The critical piece missing here would be funding for these policies and projects, because change often does not come free. There exist institutions, like the European Green Capital Award, which funds every year the city it deems to have made the most efforts in terms of climate policy. The problem remains that, by rewarding the ones that make the most efforts on climate policy, we are forgetting the others who may not have had enough money to start with that it could spend on costly “green” projects. Thus, institutions like the Covenant of Mayors should institute a more egalitarian way of providing subsidies and awards for the funding of ecological projects. Additionally, individual countries’ strategies, such as the example of Norway, are both very efficient and very expensive, and thus in future climate policy research attention should be focused both on impact and feasibility, because without a central EU agency providing egalitarian funding opportunities, progress will remain relatively slow. Not everyone can be Norway. Having said this, the EU and specifically the covenant of mayors could do a better job of centralizing information on successful strategies and creating a framework for cities to individually quickly roll out policies that have worked in the past. The Good Practices Forum for example could be less of a cache of various projects, but also be fleshed to maintain this repository, but also have specific recommended policy roadmaps for each various climate issue/angle. This kind of initial individualised support is what the EU should work on for now.