Sun-ah Choi

Ph. D. Candidate, University of Chicago

Friday, October 21, 4-6 p.m.

CWAC 156

Materialized Vision: The True Visage of Bodhisattva Manjusri of Mt. Wutai and Its Tenth-Century Translation in Dunhuang

Abstract:

This presentation is derived from the third chapter of my Ph. D. dissertation, entitled “Quest for the True Visage: Sacred Images in Medieval Chinese Buddhist Art.” While I deal with four different cases of Buddhist images related to the concept of the real 眞 in my dissertation, this third chapter focuses on the cult of a sculptural image of the bodhisattva Manjusri, which was once enshrined at the Hall of the True Visage (zhenrong yuan 眞容院) at Mt. Wutai.

I trace two historical trajectories related to the cult of the statue. Firstly, I examine the cultural process through which the icon became the central focus in the cult of Mt. Wutai. Located in northeastern China, Mt. Wutai has been believed as the abode of the bodhisattva Manjusri, attracting a number of pilgrims who expected to witness miraculous signs of the deity, including the manifestation of the bodhisattva in his flesh form. Through a comparative reading of various textual sources ranging from mountain monographs to pilgrims’ testimonies, I highlight the shift in the pattern of touring the mountain, from wandering and wondering in search for fleeting visions of the deity to the worship of a particular icon, which was named “zhenrong”(true appearance) and sanctified by the legend on its miraculous birth as the materialized vision of the bodhisattva Manjusri.

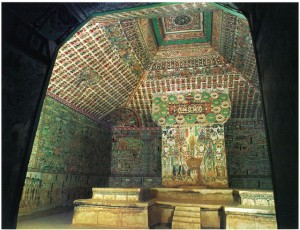

Secondly, I relate the newly arisen cult of the bodhisattva statue at Mt. Wutai to the widely-spread practice of translating the sacred space out of its cultic center. Among various examples that translated and represented the cult of the mountain, I concentrate on the tenth-century visual materials remaining at the Mogao Grotto in Dunhuang. In particular, Cave 61 serves as the centerpiece in this investigation, with a focus on the relationship between the well-known panoramic depiction of Mt. Wutai rendered on the rear wall of the cave and a statue of the bodhisattva Manjusri which once stood on the altar. By reconstructing the link between the now-missing, thus hitherto-neglected bodhisattva statue in the cave and the increasing centrality of the zhenrong icon at Mt. Wutai, I argue that Cave 61 epitomizes the critical moment in the cultic center, a moment when the ontological statuses of vision and image were conflated.