Friday, Feb.10, 4:30 to 6:30pm, CWAC156

Camp for Posthumous Life: Spatial Conception of Liao Khitan Royal Tombs

Qi LU, Ph.D. Candidate, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

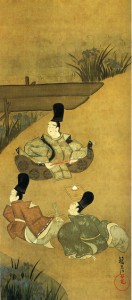

Summer Landscape, Detail of Peonies and deer, South-west Wall, Central Chamber of the Eastern Mausoleum [After Tamura Jitsuzo and Kobayashi Yukio, Keiryo (Kyoto:Kyoto daigaku bungakubu, 1953), Plate 53.]

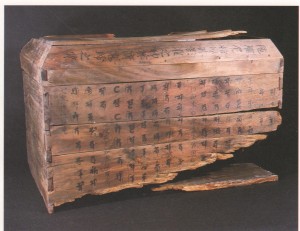

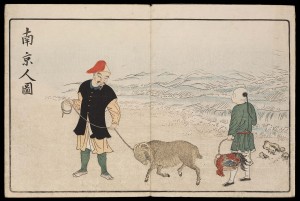

This paper explores the unique spatial conception of Liao royal tombs by investigating the murals in the Liao Eastern Mausoleum located at Qingling, with a special focus on the four seasonal landscape paintings. Though seen in tombs as early as the Han period, the landscape mural from the late Tang and Song onwards were often framed like screens that decorated the burial chamber as part of its interior furnishing. The four seasonal landscape murals installed on the four walls of the Eastern Mausoleum’s middle chamber have been discussed in the same line, but this paper argues for a different interpretation. Rather than used to help imagine an interior space, the mural’s monumental sizes and the zigzag composition with no frame that continue through all four murals immediately bring the inhabitable open field into the tomb space. As city culture flourished during the Tang-Song period, open country was conceptualized into a notion of wildness contrary to the cultivation of city. This concept of space is manifested in the pictorial programs in contemporaneous Han Chinese people’s tombs. However, the depiction of the inhabitable open country in the Khitan tombs actually reminds of their camp life and the blurry boundary between the living space and nature, interior and exterior. In the case of the Eastern Mausoleum, moving the four inhabitable hills into the tomb space in the cycle of the year, the subterranean chambers are transformed into an ideal yurt complex that is able to encamp at a different open space in each season, an effective way to bring about the nomadic lifestyle in the otherwise immobile underground space. In the later Khitan royal tombs, the yurt complex that the Eastern Mausoleum modeled after became a motif—a small-scaled replica—prevalently portrayed on the walls of the tomb passages. Rather than merely a model of the ideal structure, the yurt complex is placed on the camel chariot. Thus the logic reverses: people did not directly bring the mountains and trees into the tombs as seen in the Eastern Mausoleum, but the chariot, with the ideal yurt complex on it, is a movable home that allows the deceased to leave the “camp” and to move to the vast inhabitable open country outside the tomb. In other words, the pictorial program in the tomb over the Liao period in a sense turned the permanent underground space into a temporary camp for the emperor’s posthumous life.

Friday, Feb.10, 4:30 to 6:30pm, CWAC156

Persons with concerns regarding accessibility please contact Yunfei Shao(yunfeishao@uchicago.edu) or Zhiyan Yang (zhiyan@uchicago.edu)