By Clare Kemmerer, Dannie Griggs, Maya Ordonez, and Kaedy Puckett

Part I

How did medieval viewers experience martyr stories? Were they fascinated by the lurid details of martyrdom–the grievous bodily harm, the horrifying demons, the beautiful virgins? Did they become afraid or inspired, measuring themselves up to an unmeetable example of Christian virtue? Were they spiritually transported, or were they something nearer to a modern superhero story, a fanciful legend full of monsters and divine rescues? Images give some lens into how these stories may have been experienced: one need only look at a gruesome image of St. Agatha, her breasts torn from her by pincers, or of St. Sebastian, pierced by arrows and writhing in agony, to begin to see a strange correlation between pleasure, pain in divinity. Artists, especially in the late Middle Ages, were fond of depicting martyrs as young, beautiful virgins, subjected to terrible pain. Pain and gruesome torture may have been familiar elements of medieval cultural landscapes (they are certainly common across literature and art). But as Robert Mills suggests in his book Suspended Animation: Pain, Pleasure and Punishment in Medieval Culture, the sensuality of pain–as imagined by the medieval viewer, aided by text and illustration–may have bordered on masochistic pleasure, on fantasy, on considerations of the body that departed from the strictly pious meditation on the purity of the martyr and the severity of their suffering. The sexuality of medieval martyrs has certainly taken root in the modern imagination, as in Yukio Mishima’s Confessions of a Mask (1949), where the author records his arousal felt while gazing upon an image of the young Saint Sebastian, his body pierced all over by arrows.

Mills makes a strong argument for the possibility of medieval fantasy borne out by images and stories of martyrs undergoing torture; there’s no need for me to transcribe his argument at length. Instead, I wish to use his evocation of the sensual potential of martyrdom to examine the life of St. Margaret. The text of Margaret’s “Life” allocates agency and violence to a range of characters: to a Roman man, who is interested in her body; to the men who torture and eventually execute her, and to beasts and demons. But violence is also allocated to Margaret: she stomps on the devil, cuts her way from the belly of the dragon, and eventually begs the executioner to behead her with such forceful piety that he is compelled and, after completing the act, falls upon his own sword. If Margaret’s story provoked “responses [that] did not always organize themselves coherently in support of the ideology in question”, such responses may have included flights of fancy based largely in Margaret’s violent agency. If, as Mills argues, medieval viewers may have been voyeuristically interested in the elements of the martyr’s pain–might viewers have also been interested in their power? Though the torture Margaret faces in her “life” is clearly intended to dehumanize her, the work is full of expressions of her agency, faith, and self–and the author explicitly writes the circumstances of her execution to reflect her own conscious engagement with violence (both in the violence directed at her and that which the executor carries out against himself).

She is a conscious martyr: she speaks directly of herself as such, referencing the book of her martyrdom and (via the innovations of her author) her relics. Her “life” is explicitly interested in creating cult activity around her, unselfconsciously so. Perhaps this play of agency and violence was equally–if differently–titillating to medieval audiences. The fantasy of Margaret as both beautiful victim and powerful agent is particulalry demonstrated in the many medieval images of her which survive, few of which depict her partially naked or injured, the circumstances which for Mills imply sensual imagination (such images might include St. Lucia, holding her eyes, or St. Agatha, with her mutilated breasts). Instead, Margaret is most frequently depicted as a beautiful woman astride a dragon, slicing through it with her crucifix. Perhaps fueled by the agency displayed by Margaret, medieval artists chose to display her at a moment of explicit triumph, rather than in a moment of suffering or humiliation. The “fantasies” possible from her story depart from a fixation with the body and the body’s destruction to engage instead with miraculous self-fashioning, with explicit victory and conscious pain.

Divine

Beautiful youth

Titillating image

The tortured flesh of innocence

Engraved

Part II

In St. Margaret I was intrigued by the role of sound, or rather how the perception of sound was conveyed throughout the text. I was especially curious about the insult “deaf and dumb” that appeared numerous times. The first time it was used was on page 119 in St. Margaret’s rebuttal against the women who try to convince her to marry the prefect. She knows that if she marries him she will have to worship his God, but she says she will never “pray to your god, who is dumb and deaf.” (119). She uses this same insult against the prefect again on page 129. Finally, in St. Margaret’s final prayer she implores God that wherever the book of her matrydom is kept, “may there not be born a child who is blind or lame or dumb or deaf or afflicted by an unclean spirit” (133). This puts deafness on the same level as an “unclean spirit.”

I thought it was really interesting that deafness was used as an insult, and have a few ideas why it may have, although I would love to hear other people’s opinions on it. People who are deaf rely on sight and touch to make sense of the world. They communicate to others through facial expressions and hand gestures thus deeming them incapable of communicating with others in the dark. Those farthest from God are often perceived to exist in the absence of light. Since those who are deaf cannot communicate when there is no light to be found, they have no way of reaching God to be saved/released from the darkness. St. Margaret does give reason as to why the insult of a “deaf god” is so disparaging; unlike “my God who quickly hears those who believe in him” a god who is deaf cannot hear those who pray, and cannot answer those prayers. By the same regard, those who are deaf have no means to produce prayers.

At the same time I find it almost contradictory that deafness was viewed as negatively as it was. The first reason can be found within the text itself when St. Margaret is told that, “whatever you have asked for shall be heard in the sight of God” (133). This directly connects vision with sound, and it puts the importance of vision over that of merely hearing. Yet, it does somewhat show that the two work in conjunction. I may also be misinterpreting the word “sight” as it could carry a different meaning, but I took it to mean vision.

Also after doing some research I found that Cluniac monks, a group founded in 910 that focused on freeing the church from secular political influence and control, viewed angels with three fundamental qualities– one of those qualities was maintaining silence. They believed that those who did not speak were less likely to sin. In this regard I would think that the deaf community would be more revered than considered sinful, but at the same time communication is more difficult for those who were deaf.

Deaf ears?

Or are they heard,

Their prayers of sacrifice?

Saint Margaret like Saint Agatha

Martyr’d

Part III

I want to give my unqualified and skeptical opinion of the narrator. In other editions of the tale of St Margaret, the reader is placed inside the cell to directly look upon her deeds whereas in the Tiberius edition that we read, we perceive the narrator perceiving Margaret, and we look through his eyes onto the scene (Benjamin Saltzman Lecture). The active role of the author in the story undoubtedly has important literary/interpretive implications, HOWEVER I can’t help but question whether the author has taken on this role for literary effect or whether his intention is more selfish.

The author inserts himself in the tale from the very beginning by repeatedly announcing his name- “I, Theotimus” and saying that he “studied a certain amount of books… have zealously considered and inquired concerning the Christian faith” (Margaret 113). The next time he inserts himself, he gives himself a noble role in the story as he was “nourishing her with bread and water”, and then witnesses her heroic events (Margaret 125). His first intrusion into the story on pg 113 passes as an attempt to authenticate himself as a narrator, but the intrusion on pg 125 is just self-gratuitous. All the other characters in the story stand by or take active part in her torture EXCEPT God and now, the narrator. Again at the conclusion, the narrator then sticks his head back into the story and gives himself credit for creating a shrine, and for giving her bread and water, and for witnessing the events (Margaret 137). This comes off as an attempt to desperately cement his involvement in the tale and have the text end with his name in the reader’s mind. Maybe I’m just hostile to a man unnecessarily inserting himself into a story which features a female protagonist, but it honestly comes across like he’s selfishly just trying to steal the spotlight. Am I being too critical?

Also, I think it’s interesting that while the narrator is touting his accomplishments, he adds to the list that he “saw all of the struggle which she had with the wicked devil” (137). I am critical of this framing of the role of a bystander/witness as honorable, and overall I think there’s a contradiction even in the idea that he wants to take an active role in the story. By making himself a character in the story and giving her bread, he is showing that he is willing to take action to help Margaret; however, the fact that he does not step in at any other point in the story shows that he has drawn the line somewhere on how much he will help her vs how much he wants to protect himself. Thus by making himself an active character he has put himself into a morally ambiguous position and demonstrated his cowardice; he is worse than the onlookers who avert their eyes at the sight of Margaret’s blood because HE MUST STILL BE LOOKING* in order to know this and because he actually knows Margaret is a child of God. He could’ve avoided this whole conundrum had he just used third person omniscient POV and not tried to steal Margaret’s spotlight.

Witness

Narrate…Observe?

Participate in want

Tell stories of heroic deeds…

Live on!

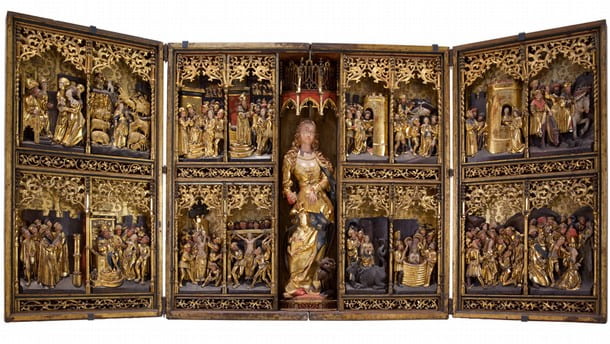

Image: Painted and gilded oak triptych known as the St Margaret Altarpiece, North Germany, about 1520. Museum no. T.5894-1859

It seems like Margaret’s are all alike. Doomed from the start no matter what their origin.