In the Liturgical Cycle for the Anglican Church, February 6, 2022 was the Fifth Sunday after Epiphany. As 2022 is Year C in the three-year cycle, the readings for the day include Isaiah 6:1-9.

[For more on Lectionary Years, here.]

In the Vulgate, verse 2 of this reading runs:

Upon it stood the seraphims: the one had six wings, and the other had six wings: with two they covered his face, and with two they covered his feet, and with two they flew.

Seraphim stabant super illud : sex alae uni, et sex alae alteri; duabus velabant faciem ejus, et duabus velabant pedes ejus, et duabus volabant.

Isaiah 6:2

This caught my notice, falling in with the podcast on the Old English Genesis and class discussions of Adam and Eve’s shame, and depictions thereof. The question of whether the fallen humans cover their faces or their genitals resonated, for me, with the angels’ ability to cover multiple body parts and, further, their apparent desire to be covering body parts in the presence of God.

First: where are all the wings? Are the angels covering their own faces and feet, or the face and feet of God (“they covered his face,” and eius is most definitely a singular pronoun)? To answer this, I looked at a couple illustrations showing six-winged beings by the throne of God: from the c.1000 Bodleian Junius 11 Manuscript to contemporary computer-generated art, visual depictions of seraphim show the angels covering themselves, to varying degrees – more on this later.

Very well then: why are the angels covering their own faces and their own feet? On the faces: to look upon the face of God is death, or an honor reserved for the most pure, worthy, perfect, etc., a theologically fraught concept in the Jewish, Christian, and Muslim traditions, if not others. Thus, to shield one’s face from God is not uncommon, and can be a gesture of respect or self-preservation in addition to (the almost toddler-like “I can’t see you so you can’t see me”) hiding one’s face from God and the world from shame. On the feet: it seems that, in the Old Testament, “feet” are sometimes used as a euphemism for “genitalia.” (And just the Old Testament! Not the New: it’s a question of language, Hebrew versus Greek/Aramaic/etc.) So here, we have an angel taking both the options we have seen for Adam and Eve in illustrations of their post fall shame: covering their face, and covering their groin.

In class, we have seen various iterations of God as the perfect, all-seeing Divine Witness, and discussed the implications of such an idea for a medieval audience. The divide, for us, has often been between God, the perfect witness, and humans, imperfect in both their ability to witness and ability to testify to their experience. These angles of Isaiah offered me a third paradigm, the angel, a witness with greater perceptive power than humanity, but who share humanity’s instinct to shield themselves, turning away and limiting their capacity to bear visual witness.

This third witness-style option, gained by parsing the biblical text and comparing it to our reading to the Old English Genesis falls apart, however, when held up alongside contemporary or later illustrations of such angels. All pre- and early-modern illustrations of seraphim that I found online give them only their head, uncovered, their three sets of wings, and few other body parts.

For example:

For comparison, here is the far earlier Junius 11 Manuscript. In this earlier version, the angels’ feet (and legs!) are clearly visible, but their feet are not:

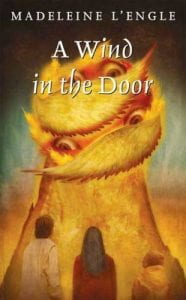

Certainly, whatever angelic need for modesty is equally preserved in these illustrations, but their faces are most definitely uncovered and often, even, directly turned to face the representation of God. A Google search for “seraphim” turns up modern results that seem more in keeping with the Vulgate description, faceless, feet- and feet-less, mostly along the lines of the Being on the cover of my childhood copy of Madeleine L’Engle’s A Wind in the Door, consisting of just wings and eyes.

For our purposes, I find this style of depiction fascinating: we have these beings who seem purpose-built to witness. Their form is centered upon their visual receptors, eyes, and their means of conveyance, wings, allowing superhuman movement and perception. This Being of L’Engle’s, posed as it is, seems to peek through its wings, in the fascination-horror attitude of a human peering through fingers at something it does not want to see but cannot bear to look away from.

For our purposes, I find this style of depiction fascinating: we have these beings who seem purpose-built to witness. Their form is centered upon their visual receptors, eyes, and their means of conveyance, wings, allowing superhuman movement and perception. This Being of L’Engle’s, posed as it is, seems to peek through its wings, in the fascination-horror attitude of a human peering through fingers at something it does not want to see but cannot bear to look away from.

Despite their differences, then, these seraphim over the ages share two key features. First, they are optimally posed to witness; whether that is due to their physical placement on either side of the throne of the omnipotent, omniscient, omnipresent, supreme witness, God; or by virtue of their physical form, primarily composed of faces or eyes, the mechanisms of visual witnessing. Secondly, they both take on self-minimizing stances, covering themselves with their wings, concealing their faces or their groin in attitudes reminiscent of fallen humanity, from Adam and Eve to a modern witness of sensational violence.

The angelic role made possible by this twofold identity, by the space they occupy between God and human, is clearly enacted in St. Paul’s Apocalypse, where angels serve in the heavenly court as guides, intercessors, advocates, and denouncers for humanity. In the saint’s testimony of his vision and experience of heaven, angels are said to watch humanity and tell God of their deeds; they carry Paul through heaven and explain what he is seeing; they sing hymns and cry out praise to God and censure of evil souls; they guard places in Hell; and they join Paul in entreating God for a day’s respite for those suffering for their worldly sins. They have a physical form, visible to Paul, as God is not; they have connections with humanity God seems not to, in their echoes of human hymns, their human-like form, and the constant company the guardian angels keep with the human on whom they are assigned to report.

Now, the theology of angels is not a cohesive doctrine, and I do not want to argue or imply that the writers of Isaiah, the Old English Genesis, and St. Paul’s Apocalypse are all picturing the same beings with the same attributes when they speak of “angels” and of “seraphs.” However, as we ask about forms of mediation and witnessing and as we consider the gravity of what we ask when we ask humans to witness evil (whether as victims or as those tasked with conveying these events to others), the “angelic” paradigm offers a firm model for those who have the strength to bear constant witness, but retain their capacity for human imperfection.

Bibliography

Latin text and translation from The Holy Bible, Douay-Rheims Version. Ed. Bishop Richard Challoner. John Murphy Company. Baltimore, MA: Tan Books, 1971. From http://www.drbo.org/, ed. Paul B. Mann

L’Engle, Madeleine. A Wind in the Door. Square Fish, 2007.

Images cited in captions.