By Eva Kinnebrew

Eva Kinnebrew is a 4th-year Environmental Studies major. This summer she was a Jeff Metcalf intern at the Marine Biological Laboratory in Woods Hole, MA, where she studied grassland ecology.

Naushon Island, the largest of the Elizabeth Islands off Cape Cod, has a fascinating ecological legacy. Historically it was wooded, but following European colonization in the seventeenth century, much of the forest was cleared to create fields for livestock grazing. The process of cattle and sheep grazing transformed the landscape into an open rolling grassland, which supported a very different ecosystem than that of the pre-existing woods1.

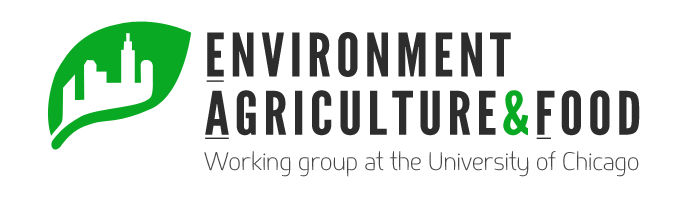

Disturbances like grazing are important for the maintenance of ecological stability and the preservation of biodiversity2. Thus, the removal of the Naushon Island livestock in the nineteenth century greatly upset the ecosystem balance. With the absence of grazers, the Naushon grasslands have begun the process of ecological succession: thick, woody shrubs are invading onto the grasslands and outcompeting the grasses there3. Some of the older islanders have told us that when they were kids, in the 1930s and 40s, the land was open and they ran about it, free. Now the shrubs have made something of a maze of the island – creating a series of hedges through which one has to strategically zigzag in order to get anywhere. Many parts of the island, like the patch in which my co-worker Lena Champlin (Brown University) is standing in Figure 1, are completely impassible.

Figure 1: In this photo, Lena stands in a patch of catbrier, or Smilax rotundifolia. While some grass plots can have up to 20 species, many shrub plots, like this one, contain only one or two species.

While the process of shrub invasion is natural and the invading shrubs are native, rather than allowing ecological succession to continue, many scientists and conservationists have advocated for the protection of the grasslands3. Even though the ecosystem is, indeed, man-made, the grasslands are incredibly diverse in both plant and animal life. Grasslands are especially important to conserve because they have suffered a dramatic decline in North America due to pollution, development into urban areas, and conversion to cropland4. Preserving the remaining grasslands, then, is key to protecting the species that live there.

This summer, I have been studying Naushon Island and its expanding shrubland at the Marine Biological Laboratory (MBL), a research institution on Woods Hole, MA which, as of 2013, is formally affiliated with the University of Chicago. The MBL started a long-term study of Naushon Island in 2012 in order to better understand the mechanism of shrub growth. The main goal of the study is to test the efficacy of possible management techniques, such as grazing and mowing. In our experiment, we have implemented both grazing and mowing in varied intensities and combinations to see how this affects the rate of shrub spreading and biodiversity.

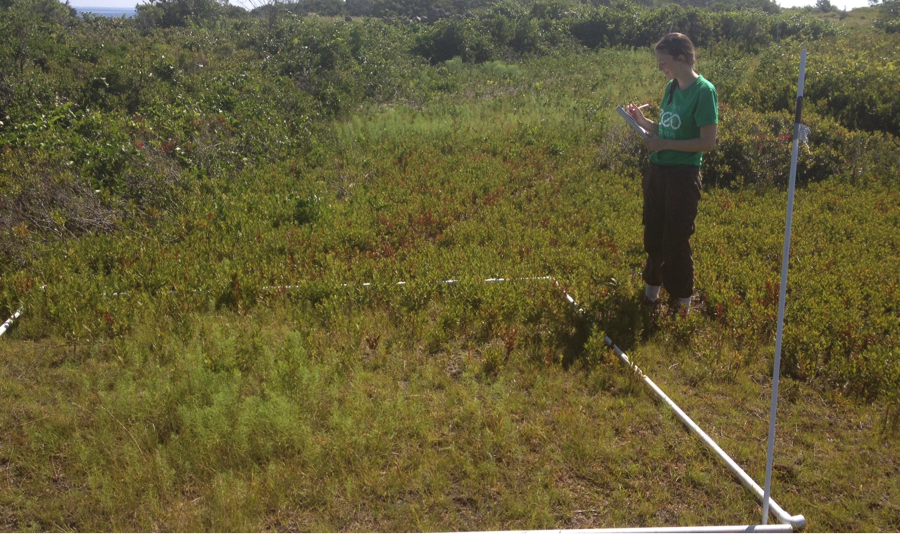

On a normal day, my two coworkers (who are also undergraduate interns) and I take a thirty-minute ferry from Woods Hole to Naushon Island. We then drive our field truck about five miles up the island to one of our two field sites, Lighthouse Pasture or Protected Field. In these sites we do a number of tasks. We devote some days to monitoring vegetation (Figure 2), which involves setting up a 3m by 3m plot, identifying every plant in the plot, and estimating its cover. For example, we may say a plot is 50% Smilax rotundifolia (catbrier) and 50% Gaylussacia baccata (huckleberry). The team monitors these plots every year so that we have a record of how the species composition changes over time. Learning to identify all the plants on Naushon Island has been one of the most challenging and fun elements of the internship.

Figure 2: In this photo, Lena stands outside a vegetation monitoring plot and records the species composition. This plot is an “edge plot,” meaning that it is on the edge of an encroaching huckleberry patch. These plots are very useful because they allow us to calculate the rate of shrub spread.

Other days in the field we may spend wrangling cattle, setting up fences, mowing, or taking biomass samples. There is a lot of variation in our work, which keeps the project interesting.

My independent project this summer involves studying the relationship between soil nitrogen (N) and species composition. Specifically, I want to know how nitrogen in the soil can impact plant species richness, or the number of species on the land. Soil nitrogen levels in the Northeastern United States have risen significantly above pre-industrial levels as a result of increased N deposition from intensive agriculture and fossil fuel combustion, and although the Clean Air Act of 1963 and later amendments have reduced the release of atmospheric N, soil levels remain elevated5. Scientists have found that high levels of soil nitrogen impact grasslands because these native grasses have evolved in low nutrient environments and can be outcompeted by fast-growing species, such as catbrier and huckleberry, in the presence of high soil N6,7. Perhaps this is what we are seeing on Naushon Island.

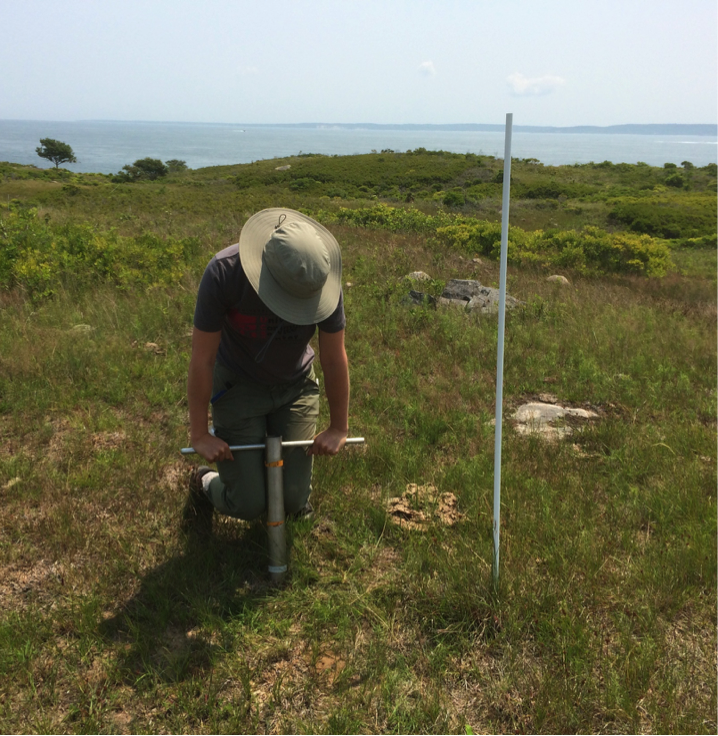

To test this, I collected soil in plots where vegetation monitoring has been done and then analyzed the soil for both ammonium and nitrate. This will allow me to compare soil nitrogen levels to species richness and detect whether there is a trend.

Figure 3: Here, I take a soil core in a grass plot in Lighthouse Pasture. Our soil cores are 15cm deep and 5cm in diameter.

I am hoping this study will help answer the question of why the shrubs are so successful where they are. My project is also fascinating in that it can show how our treatments, grazing and mowing, impact soil chemistry. All of the analysis from this study will be completed during this upcoming academic year as part of my senior thesis for the Environmental Studies major.

To close, I want to briefly discuss the implication of the nitrogen to species richness relationship. If high levels of nitrogen can lead to lower species richness, then what does this mean for post-agricultural lands, where soil is typically very rich in nitrogen due to years of fertilization? After these lands are abandoned, can they ever recover into the diverse grasslands that they once were, or have humans fundamentally altered the kinds of plant life that these lands can support? I think these questions are very important for the future of agriculture and land restoration.

1. Foster, D.R., and Motzkin, G. 1999. Historical Influences on the Landscape of Martha’s Vineyard: Perspectives on the Management of the Manuel R. Correllus State Forest. Harvard Forest, Harvard University: Petersham, Massachusetts.

2. Hobbs, R. J. and Huenneke, L. F. 1992. Disturbance, Diversity, and Invasion: Implications for Conservation. Conservation Biology, 6: 324–337

3. Motzkin, G., and Foster, D.R. 2002. Grasslands, heathlands and shrublands in coastal New England: historical interpretations and approaches to conservation. Journal of Biogeography, 29, 1569–1590.

4. White, R., Murray, S., and Rohweder, M. 2000. Pilot Analysis of Global Ecosystems: Grassland Ecosystems. World Resources Institute: Washington D.C.

5. Templer, P.H., Pinder, R.W., Goodale, C.L. 2012. Effects of nitrogen deposition on greenhouse-gas fluxes for forests and grasslands of North America. Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. Vol. 10, No. 10, 547–553.

6. Nagel, L. 2005. Use of Soil Carbon Amendments on a Martha’s Vineyard Grassland Restoration Site. Master’s Thesis, Allegheny College: Meadville, PA.

7. Polatin, C.C., 2006. Best Management Practices for Controlling Catbrier (Smilax rotundifolia) Oriental Bittersweet (Celastrus orbiculatus), and Scotch Broom (Cytisus scoparius) on a Coastal Island in Massachusetts. Master’s Thesis, Antioch University New England: Keene, New Hampshire.