Chicago as an Incubator for Self-Taught Art: The Individualistic Life and Work of Joseph E. Yoakum

Vicky Chen

Artistic careers do not usually start at the age of 71, but Joseph E. Yoakum had never been one to follow what was expected or typical. Born in Ash Grove, Missouri to parents of African American, Cherokee, and European ancestry, his visual imagination was fed by his early days working with travelling circuses that took him all over America and abroad until around 1908. After serving as a soldier in France during World War I, he continued to wander for nearly two decades, saying, “Wherever my mind led me, I would go. I’ve been all over this world four times.”[1] After settling down in Chicago in the 1930s, his later “travels” occurred mostly through his drawings. Yoakum famously describes his creative process as one of “spiritual unfoldment,” meaning that the spirit and subject was slowly revealed to him as he worked.[2] Yoakum drew inspiration from his firsthand experiences of travel and far-flung locations, popular culture sources like the Encyclopedia Britannica, and his imagination, constructing landscapes infused with a memory, myth, and spirituality. He worked consistently with the same materials—most notably his ballpoint pen—and his unique creative journey lives on in the Chicago art scene of today. While investigating the work and artistic studies of Joseph E. Yoakum, there arises connections about the space-based relationship between Chicago as a city and the individuality of self-taught artists that flourished in it.

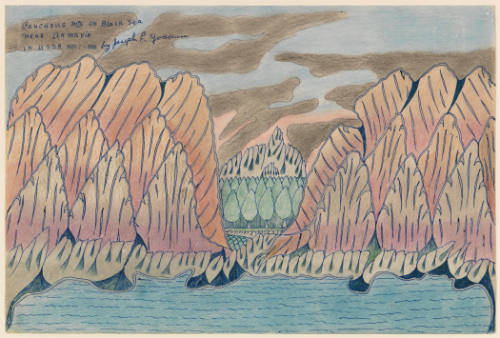

There are many ways to study and analyze Joseph E. Yoakum, but the best way would likely be visually, through the works he created to define his lifetime of travels, feelings, and imagination. Using striated lines and undulating shapes, Yoakum created thousands of landscape drawings over his lifetime. His work was based directly off his extensive travels as a soldier and member of the Buffalo Bill Circus, as well as his own personal mythology. As Art Institute of Chicago curator Mark Pascale aptly describes, “while a drawing might resemble general or specific features of a place in his professed travel itineraries, what matters most in the end is how Yoakum drew it.”[3] His influential construction of flat space, which can be seen in the drawing on display in this exhibition, is due to a unique use of line, color, and patterns to create swelling mountains, overlapping trees, and all the natural flows, ridges, and irregularities of nature. During his passionate period of creation, Yoakum used this playful and idiosyncratic style as the language to communicate the feeling and spiritual remembrance different sites evoked for him, instead of focusing on likeness and accuracy. Yoakum famously explained, “My drawings are a spiritual unfoldment.” Through his drawings, we get a sense of his values and what he takes to be important. There is not really a sense of scientific realism, but instead, a focus on rendering the feeling and spirit of the area or picture he is trying to depict.

The drawing on display in this exhibition, the Caucasus Mts On Black Sea near Urmarvin in USSR (1984), was created with a ball-point pen and colored pencil on paper and measures 11 7/8 by 17 7/8 inches, a size typical for Yoakum’s works (fig. 1). His trademark freehand pen illustration, interlapping shapes, and tree grouping pockets all play a role in this piece. Although nonscientific and aesthetically disproportionate, Yoakum’s sketching, shading, and outlining does a successful job at conveying and translating the impressive sight of the Caucasus Mountains rising above the sea, which is an accuracy within itself. The mountains seem to sit directly on the water, creating an interesting tension with the lack of transition between different types of Earth form and topography. His undulating lines and forms depict natural forces like mountains and seas not as solitary but conjoined forces. That being said, it is unknown whether Yoakum ever visited this site, something characteristic of his practice. As the catalogue of the Art Institute of Chicago’s recent exhibition, Joseph E. Yoakum: What I Saw (2021), put it: “Whether the artist had ever been to these places is unknown, and because of his penchant for stretching the truth, we may never know. But when it comes to his work, that may not be relevant.”[4] He executes these freeform landscape drawings with incredible storytelling ability that translates his admiration of the natural world, whether he had witnessed this specific site in person or only through his imagination. Although disproportionate, he conveys the force and scale of the elements he depicts, creating an animated and reverent vision of nature.

Fig. 1. Joseph E. Yoakum, Caucasus Mts On Black Sea near Armavir in USSR. 1964, ballpoint pen and colored pencil on paper. Gift of Dennis Adrian in memory of George Veronda, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 2001.571.

Having never received formal artistic training, Yoakum is often discussed as a self-taught artist. He employed simple materials—notebooks, tracing paper, ballpoint pens, among other commonly available supplies—and began making art suddenly and enthusiastically. In her poem “Yoakum’s Hoakum,” Carol Boston Weatherford describes the quick inception: “One night he woke up ill. Sweaty-palmed, he grabbed a pencil, sketched a vision. Golgotha; his first drawing. Followed by one a day for eight years.”[5] This did not stop him from developing a personal artistic vision, but rather, encouraged it. The prolific body of work he created during his short period of passionate activity—totaling around 2000 drawings—used simple materials to create a highly personal vision of incredible beauty. Creating with such fervor, Yoakum was able to define his style and tone quickly—it evolved and changed throughout his decade of activity, but remained loyal to the same simple materials he used in the beginning: everyday materials like ballpoint pens, stamps, and colored pencils.

The majority of Yoakum’s works featured landscapes. The curator of Yoakum’s recent retrospective at the Art Institute of Chicago, Mark Pascale, has suggested that we can consider these works a visual diary in which Yoakum depicted “where he was, where he had been, and where he hoped to go, where he felt most excited and comfortable, and where he felt he lived the most.”[6] Another fascinating visual element included in many of his works is the inclusion of a hand-written title on the top left corner. The information given by these titles is specific, assigning a place and time to the landscape depicted while at the same time revealing Yoakum’s idiosyncratic voice. Yoakum also stamped and dated each piece after he had sold them, but it is said that the stamps are not always accurate due to Yoakum’s willingness to let school children play with them in his studio.[7] These everyday materials, like stamps and colored pencils, as well as the speedy artmaking process he deployed, provide a contrast to the meticulous traditional process of depicting natural elements, whether scientifically or artistically. This is not to say that Yoakum was not a detail-oriented or painstaking artist. Quite the opposite. He remained loyal to his style and materials; the consistency of the tone and feeling translated across his large volume of drawings only proves his ability to depict a wide range of areas in his own language.

Although Yoakum’s vision was unique, the context of Chicago was important to the discovery and reception of his work. Chicago has played a huge role in both promoting and embracing so-called “outsider art” as an authentic mode of artistic practice, and these conversations were ongoing during Yoakum’s lifetime. To understand the city’s role, we must first look at the geographical significance of Chicago as a city “whose purpose was to be in the middle.”[8] In the late 1940s, there was an explosion of migration and creative activity in the city, with many industries growing. Outside of Chicago, there was also shift of the artworld away from Europe towards the United States, and a loosening of the hold of art academies on the training and evaluation of art. The shift from academic training to a more open understanding of what constituted artistic practice was promoted by the French painter Jean Dubuffet in his 1951 lecture, “Anticultural Positions,” in which he argued against the Western academic canon and advocated for the consideration of artworks produced by those excluded by the academic tradition, including the work of the mentally ill, self-taught artists, and public graffiti. His talk resonated with Chicago-based artists and collectors and led to an expanded consciousness about what culture is and where it could be found; an apt concept specific to Chicago’s artistic and cultural historical situatedness between New York and Los Angeles.[9] Many critics and scholars emphasized that “Chicago artists, critics, and collectors valued risk-taking and a dedication to authentic self-expression as evidence of an avant-garde mindset.”[10] This is reflected in the personal art collections of artists like Ray Yoshida and Roger Brown, whose homes were packed all many of art objects presented densely without an immediately apparent organizational scheme (which should be regarded as an intentional statement in itself). Yoakum himself would display his clay sculptures and pieces in the window of his storefront studio on Chicago’s South Side for all those to see. Additionally, his early appreciators, such as Edward Sherbeyn, Whitney Halstead, and John Hopgood, would view his work by visiting his studio with their colleagues and students. These studio visits with his work and materials strewn all over the place are a far-cry from the manner and settings in which Yoakum’s work is presented today, but they were an integral incubator for his drawings.

Several Chicago institutions also played an important role in promoting the work of self-taught artists like Yoakum. Institutions like Hyde Park Art Center, Renaissance Society, Museum of Contemporary Art, and Chicago Cultural Center provided wider public visibility for self-taught artists beyond the core of early enthusiasts of teachers, artists, and a handful of collectors of modern and contemporary art.[11] The Hyde Park Art Center located on Chicago’s South Side was especially important to Yoakum’s career. This institution was at the time led by Don Baum, who embraced a more creative approach to curating. Baum was enthusiastic about making the Hyde Park Art Center “a place where artists who have had no previous exhibiting experience could show… The [commercial] galleries weren’t interested. Nobody knew who you were or what you did. This was the only viable working place to show.”[12] More generally, the 1960s was a difficult time for Chicago artists to navigate the art scene, as it offered only a few ways to gain critical and commercial exposure. These different forms of displaying and appreciating self-taught art in Chicago are a testament to the many ways of working outside of traditional spaces, and allow us to trace the emergence of local artistic networks that bridged academic and non-academic art.

To this point, it is helpful to consider how specific individuals contributed to the rising status of self-taught art and non-traditional viewpoints in the Chicago art scene of the 1960s and 1970s. One of the most important of these individuals was Kathleen Blackshear, who taught art history at the School of the Art Institute. Blackshear’s classes focused on finding alternatives to the Western classical tradition and its descendants, bringing works conventionally described as “non-art” into the classroom. Her student, Whitney Halstead, followed her example by advocating the value of artists whose materials and methods fell outside narrow definitions of fine art. As scholars have argued, Halstead and Blackshear’s academic positions “may account in part for the positive reception in Chicago for self-taught artists and their work.”[13] Importantly, Halstead championed Yoakum’s work and generated a greater sensitivity towards non-academic art, helping other collectors and academics recognize the value in self-taught Chicago artists and their idiosyncratic ways of depicting the world. This openness to the possibility of locating art outside museums and other authorizing institutions was also reflected in the openness of Chicago artists to “non-art” sources. The artist Roger Brown, for instance, reflected that in the Chicago art scene “one sees [comics and advertising] as art in themselves, not as something to be blown up to make art, but as something parallel in your own work. Those things are already art: so, if you can make art as good, you’re really lucky.”[14] Brown was an important early collector and promoter of Yoakum’s work, which was greatly admired by the loose group of artists known as the Chicago Imagists.

Roger Brown famously described “finding” Yoakum, saying “I could not believe the appearance in our midst of Joseph Yoakum, Chicago’s own Henri Rousseau.”[15] When thinking about Yoakum’s reception, it is important to pay careful attention to the words “finding” and “discovering” employed by his admirers, which walk a thin line between popularizing and tokenizing his work. This dynamic is often at work in discussions of self-taught art, but in the case of Yoakum it is additionally complicated by his identity as a Black artist living and working in a highly segregated urban and artistic environment. The disparity between Yoakum’s position and that of the circle of white critics and artists associated with the Chicago Imagists and Hairy Who, who were his works most passionate promoters, has led some to suggest that Yoakum’s work was co-opted and tokenized by this group. This concern was addressed explicitly in an article that appeared in an issue of the New Art Examiner (an art criticism magazine based on Chicago’s South Side) from the 1970s. In this article, the critics Derek Guthrie and Jane Addams Allen voiced their skepticism about Yoakum’s reception, arguing that members of the Hairy Who had exploited and then abandoned the artist (a claim that has since been nuanced by scholars, who noted the lifelong commitment of these artists to promoting Yoakum’s work).[16] Nonetheless, Guthrie and Allen’s skepticism raises questions about how the meaning of Yoakum’s work changes as it moved from the informal storefront space of his studio to be hung in private collections, white-owned galleries, and eventually museums. It is said that Yoakum was wary of the art world and nervous of getting taken advantage of by its power players and institutions.[17] The difficulty of negotiating with the museum as a black artist is highlighted in the catalogue of the recent MoMA exhibition, Among Others: Blackness at MoMA, which notes that although the museum is often “in conflict with art,” this conflict “only deepens when something about an artwork’s creator differs from the going norm: white, male, and oriented to art’s established routines.”[18] Yoakum’s work gained acceptance in the Chicago’s art world after his “discovery” by critics like Halstead and artists like Brown, who valued his “outsider” status and the unique perspective it gave his work. However, the language of “finding” and “discovery” can also be problematic, insofar as it risks reinforcing the historical marginalization of non-white, non-male, and non-academic artists.

While it is true that Yoakum’s work is unique and extraordinary, using exclusive language to call his work exceptional can create a problematic discourse. It raises questions about how exactly art is valued and risks implicitly accepting the idea that, when it comes to art created in non-white and non-academic contexts, finding great art is an exception instead of an expectation. Yoakum himself was aware of this and expressed concern about being described as an African American artist [in exhibition].[19] This statement not only suggests Yoakum’s awareness of the way his identity could impact the way his work was received and valued, it also speaks to his own complicated relationship to his African American heritage. Yoakum notably distanced himself from the active Black artistic scene on Chicago’s South Side, and described himself as a “Nava-joe,” punning on his claimed Native American ancestry. More recently, scholars have suggested that Yoakum’s insistence on his Native American over African American ancestry was perhaps an attempt to “transcend the harsh realities of urban division.”[20]

Although a larger interest in recognizing non-mainstream art by Chicago’s artistic players and spaces propelled Joseph E. Yoakum’s work into popularity, Yoakum’s work continues to speak for itself and evolve in its originality. Yoakum’s work transcended borders, not only of the physical locations he depicted, but culturally and artistically; his individualism in all aspects of his work and self-styling was the driving force behind the beauty of his work. Yoakum’s idealized landscapes with their vast, swelling natural forms reflect his own spirit: grand and generous and spiritual. In an essay published three years after Yoakum’s passing, Halstead aptly described the way, in Yoakum’s work, fact and fantasy come together in the service of the same goal of depicting his life and dreams through landscape. His experiences, spiritual beliefs, and work are deeply intertwined together. Ultimately, the singleness and authenticity in his work can be attributed to the absolute individuality that Yoakum fiercely maintained throughout his life of real and imagined voyages across the world.

—

- Jane Allen and Derek Guthrie, “Portrait of the Artist as a Luckless Old Man,” Chicago Tribune Magazine (December 10, 1972).

- Gerard C. Wertkin et al. Self-Taught Artists of the 20th Century: An American Anthology (New York: Chronicle Books, 1998), 111.

- Mark Pascale, Joseph E. Yoakum: What I Saw (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2021), 7.

- Taylor Dafoe, “How Joseph E. Yoakum, an Enigmatic Former Circus Hand and Untrained Artist, Found Drawing in His 70s—and the Hairy Who as Admirers,” Artnet News (July 21, 2021), 15.

- Carole Boston Weatherford, “Yoakum’s Hokum,” Obsidian: Literature in the African Diaspora 10, no. 2 (2009): 225.

- Pascale, 52.

- Garvey, Timothy J. “Garden Becomes Machine: Images of Suburbia in the Painting of Roger Brown,” Smithsonian Studies in American Art 3, no. 3 (1989), 18.

- Kenneth C. Burkhart and Lisa Stone, Chicago Calling: Art Against the Flow (Chicago: Intuit, the Center for Intuitive and Outsider Art, 2018), 26.

- Maggie Taft and Robert Cozzolino (eds), Art in Chicago: A History From the Fire to Now (Chicago: the University of Chicago Press, 2018).

- Robert Cozzolino, Art in Chicago Resisting Regionalism Transforming Modernism (Philadelphia: Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, 2007), 10.

- Archived didactic text from the Smart Museum of Art’s exhibition, Outside In: Self-Taught Artists and Chicago (2002).

- Taft and Robert Cozzolino (eds.), 166.

- Ibid., 155.

- Ibid., 142.

- Roger Brown, La Conchita, CA, 1995.

- Burkhart and Stone, 26.

- Ibid., 27.

- Darby English and Charlotte Barat (eds), Among others: Blackness at MoMA (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 2019), 474.

- Pascale, 7.

- Ibid., 55.

—

This site is for educational purposes only. Certain images on this website are protected by copyright and may be subject to other third party rights; downloading for commercial use is prohibited.