Der Tierlaokoon: Anthropomorphism Takes the Stage

Ellis LeBlanc

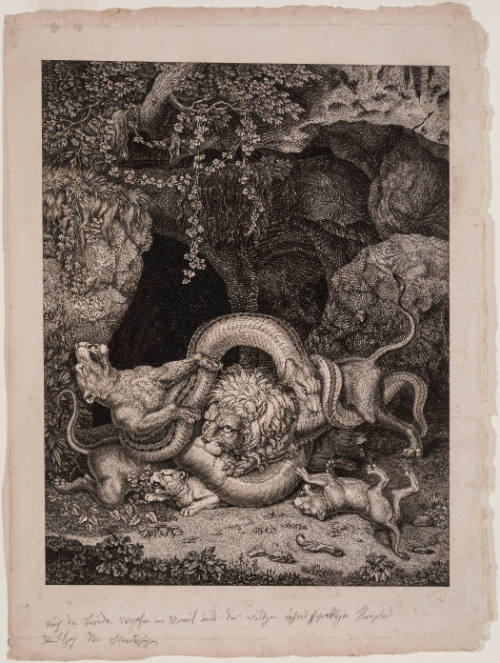

Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein’s Der Tierlaokoon (The Animal Laocoön, 1796) is an etching on laid paper measuring 21 ⅛ x 15 ¾ inches and was gifted to the Smart Museum of Art by Stephen and Elizabeth Crawford in 2016 (fig. 1). The etching depicts a reimagining of the Laocoön myth from Greek mythology, which tells the story of a Trojan priest of that name who disobeyed the sun god Apollo. As punishment, Apollo sent a giant snake sent by the god to kill Laocoön and his two sons.[1] Tischbein’s print reimagines the scene as a conflict within the animal world. It depicts a battle scene frozen in time where a family of five lions, an zoomorphic version of Laocoön and his family (with the addition of a lioness and extra cub), wrestles with the antagonist of the myth. An inscription—hidden by the current matting—sits below the image and reads “Das Löwenpaar im Kampfe mit der Riesenschlange oder der Tierlaokoon” which translates to “the pair of lions fight with the giant snake, or The Animal Laocoön.” Although it is unclear who wrote this inscription, this inscription reflects contemporaneous discussions of Tischbein’s print and offers an important context for the work by drawing attention to relationship to the Laocoön myth and its famous representation in the Laocoön Group sculpture, one of the most celebrated works of classical antiquity (fig. 2). In addition, it also gestures to Tischbein’s preoccupation with anthropomorphism and zoomorphism, raising the questions about human’s relationship to the animal world.

Fig. 1. Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, Der Tierlaokoon (The Animal Laocoön). 1796, etching on laid paper. Gift of Stephen and Elizabeth Crawford, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 2016.106.

This essay explores the significance of Tischbein’s reinvention of the Laocoön myth and its representation in classical sculpture. It will begin by examining the history of the Laocoön Group sculpture and its significance in the art historical and antiquarian debates of Tischbein’s era. It will then situate Tischbein’s print in relation to the artist’s larger interest in the process of anthropomorphism and zoomorphism. Finally, it will consider the significance of Tischbein’s decision to embed the Laocoön myth within a in a stage-like context that seems to prefigure the natural history dioramas of the late nineteenth century, reinforcing a larger interest in the relationship of the human and natural worlds.

Fig. 2. Attributed to Athanodoros von Rhodos, Hagesandros und Polydoros, The Laocoön Group (also known as Laocoön and His Sons), 30-40 B.C, marble. Vatican Museums, Vatican City.

As an artist steeped in the antiquarian traditions of German neoclassicism who trained and worked in Italy, Tischbein was deeply aware of the conversation surrounding the Laocoön Group sculpture, which currently resides in the Vatican Museum in Rome. The sculpture, also known as Laocoön and His Sons was created between 40-30 BCE during the Hellenistic period.[2] According to the Vatican Museum’s records, the sculpture was acquired for the Vatican by Pope Julius II upon its excavation in 1506 near Rome. Its rediscovery prompted much excitement, particularly since the sculpture’s apparent naturalism corresponded to the preoccupations of contemporaneous developments in the rendering of the human figure amongst Renaissance artists. The sculpture subsequently occupied an important place in the work of later generations of scholars including Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, and Johann Wolfgang von Goethe (a personal friend of Tischbein), and thus became a corner stone in aesthetic theories of the eighteenth century.

Even before its rediscovery, the Laocoön Group occupied an important position in European antiquarian and artistic culture. Before its rediscovery, it was known primary through the Roman natural philosopher Pliny the Elder’s discussion of the sculpture in Book 36 of The Natural History (77-79 CE), which served as a key source for early modern knowledge the classical world.[3] Pliny, who encountered the Greek sculpture in the palace of the Roman Emperor Titus, praised the sculpture as “preferable to any other production of the art of painting or statuary.”[4] Because of Pliny’s assessment, the rediscovery of the Laocoön Group in the early sixteenth century was a momentous affair. Suddenly, a supposedly lost masterpiece was found and put in an institution of power, where it could be contemplated by political, artistic, and intellectual elites. To give credit where it’s due, Pliny’s description is accurate—the sculpture remains stunningly beautiful and conveys the drama of the myth incredibly.

During the eighteenth century, the scholars Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, and Johann Goethe each wrote on and expanded upon the potential interpretations of the Laocoön Group.[5] Winckelmann interrogated the sculpture from a purely aesthetic viewpoint as evidence of the “calm grandeur” (stille Größe) of classical sculpture.[6] At the center of Winckelmann’s argument was the sculpture’s at once expressive and restrained depiction of pain, which the scholar later elaborated upon in in his History of the Art of Antiquity (1764):

“Laocoön is an image of the most extreme suffering, which acts here on all the muscles, nerves, and veins; the blood boils intensely from the deadly bite of the serpent, and all parts of the body express exertion and pain, whereby the artist made visible every impulse of nature and displayed his great science and art. In the representation of this extreme suffering, however, we see the well0tested spirit of a great man, who struggles against extremity and who seeks to quell and stifle the eruption of feeling.”[7]

Ultimately, Winckelmann argues that it is in this tension between the extremities of emotion and noble restraint that constitutes the sculpture’s achievement.

Picking up where Winckelmann left off, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing’s Laocoön (1766) used the sculpture to argue for a distinction between the poetic and pictorial arts. Lessing developed this schema in response to Winckelmann’s notion that the quiet grandeur of the sculpture conveyed the caliber of Laocoön’s soul, which allowed for the figure to overcome his intense pain. Lessing, however, argued that the restraint the sculptor showed in depicting Laocoön’s scream was due not to stoicism, since, as he argued, the scream emitted in moments of bodily represented the height of tragedy in Greek poetry and drama.[8] Instead it was due to the fact that the visual depiction of such extremes of emotion resulted in the “most hideous contortions” and thus contradicted the criteria of beauty:

“Simply imagine Laocoön’s mouth forced wide open, and then judge! Imagine him screaming, and then look! From a form that inspired pity because it possessed beauty and pain at the same time, it has now become an ugly, repulsive figure from which we gladly turn away.”[9]

Thus, in the Laocoön Group, the sculptor “strove to attain the highest beauty possible under the conditions of physical pain. […] The scream had to be softened to a sigh, not because screaming betrays an ignoble soul, but because it distorts the features in a disgusting manner.”[10]

Tischbein would have been intimately familiar with Winckelmann and Lessing’s interpretations of the Laocoön Group sculpture, and this debate about the meaning of Laocoön’s scream (or lack thereof) is important to his print. That being said, Goethe’s discussion of the sculpture, first published in 1798, only two years after Tischbein’s print was created, is perhaps more relevant to understanding Tischbein’s etching, not only because the two men were friends, but because he expanded upon the debate inaugurated by Winckelmann and Lessings’s work.

Whereas Winckelmann and Lessing viewed the central figure as akin to a tragic hero, Goethe’s commentary’s humanized and naturalized the sculpture’s figures. As William Guild Howard has argued, Goethe’s text treated the sculpture’s theme as a “tragic idyll,” casting the snakes that assailed Laocoön and his family not as “divine agents of destruction, but natural creatures,” and the family themselves as “human beings shorn of every other characteristic than strength and comeliness of person, and membership in one and the same family.”[11] By deemphasizing the mythical, Goethe’s commentary thus not only transformed the figure of Laocoön into a type—the father—it also rendered him tangible and relatable to contemporary viewers. The plight that Laocoön faced thus became something closer to the viewer’s own experiences with fear when faced with the dangers of the world. For Goethe, this was what made the work so powerful: he acknowledged its aesthetic achievement, but at added a new dimension to Winckelmann and Lessing’s interpretation by embedding Laocoön’s plight within the natural world.

This effort to naturalize the tragic myth can be situated in relation to Goethe’s larger interest in natural history, especially his Metamorphosis of Plants (1970), which offers additional insight into the operations of metamorphosis at work in Tischbein’s print. In this text, Goethe put forward the notion that there is an Ur-plant, which he imagined as the origin of all vegetal, and perhaps even animal life.[12] Goethe was deeply interested in the possibility of animal organisms developing out of vegetal matter, and even conducted his own experiments on the subject. There is some debate about whether Goethe actually believed the Ur-plant could be found in nature or existed as an ideal form, however he report searching for it while traveling to Italy, where he became friends with Tischbein.[13] Moreover, in addition to his interest in the development of animal life from plants, Goethe also argued for anatomical continuities between humans and animals.[14]

Although it is unclear whether Tischbein was familiar with Goethe’s interpretation of the Laocoön myth at the time he made his print, it seems probable that the two men might have discussed Goethe’s thinking while visiting the monuments of classical art in Italian collections, as well as his thinking on the continuities between the vegetal, animal, and human, a subject that Goethe was actively working on during the same period. The print itself certainly does seem to engage and intensify both aspects of Goethe’s thought. With the Tierloakoon, Tischbein does not simply humanize the figures of Laocoön and his sons, but naturalizes them by transforming them into a family of lions and embedding them in lush natural environment. The use of zoomorphism allows the artist to probe and intensify what made the original sculpture so dramatic and striking—at least in the Goethean vein of thought, since it is doubtful that Winckelmann or Lessing would have approved of this iconographic shift, which risked lowering the epitome of human nobility into the animal world.

Although conversations with Goethe may have informed Tischbein’s approach, the artist’s decision to adapt the Laocoön theme was likely primarily motivated by the sculpture’s significance to the artistic and intellectual community of the eighteenth century. The sculpture’s fame allowed for an easy recognition of its principle traits and features, and also represented a bold gambit for testing the boundaries of anthropomorphism (the projection of human traits onto animals) and zoomorphism (the projection of animal traits onto humans), two processes in which Tischbein was highly interested.

Tischbein produced a large number of drawings and prints focused on animal figures. Many of these appear to be studies for a print portfolio called Têtes de différents animaux dessinées d’après nature pour donner une idée plus exacte de leur caractères (1796), in which the artist explored the characteristics and attributes of animals and undertook to transform a number of historical personalities including the Roman hero Scipio and Emperor Caracalla, the artists Michelangelo and Corregio, and even the gods Apollo and Jupiter into animal figures (fig. 3-5).[15] The Tierlaokoon in fact served as the opening plate of this portfolio, which Tischbein published during his tenure as Director of the Royal Academy of Painting in Naples.[16] When situated in this context, the Tierlaokoon takes on a radically different meaning. More than simply a response to a larger art historical conversation—as I suggested earlier—the etching also functioned as a methodological exercise for an artist deeply interest in ideas of comparative physiognomy, which sought continuities between the anatomy and attitudes of humans and animals.[17] In this context, the Laocoön theme above all provided Tischbein with an iconic and easily recognizable motif for his experimentation.

Figs 3-5. Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, Têtes de différents animaux dessinées d’après nature pour donner une idée plus exacte de leur caractères. 1796, etching.

As art appreciators, we are perhaps familiar with the genre of sketches and studies that artists made prior to taking on a larger project, such as the studies for Renaissance or the numerous sketches and studies done by artists like Dégas and Cézanne. In Têtes de différents animaux dessinées d’après nature pour donner une idée plus exacte de leur caractères, Tischbein actively included the audience in the practice of creating studies. The majority of these studies are heads of animals rendered in incredible detail against a monochrome, empty background. The emphasis lies on the artist practicing and working through his ideas and interest in exploring how to better depict animals as individual beings. Based on the documentation of the work he’s most well-known work, Goethe in the Campagna (1786-87, fig. 6), we know that Tischbein was highly methodical and worked through his ideas in great detail before creating the finished product.[18]

Fig. 6. Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, Goethe in the Campagna. 1786-87, oil on canvas. Städel Museum, Frankfurt am Main.

With this in mind, we can now shift focus to the Tierlaokoon itself. Looking at the print, our gaze is immediately met with the incredibly dynamic, violent, and dramatic scene. The composition’s focal point is the family of lions beset by the giant snake. The drama unfolds at the mouth of an inky black cave whose interior is left to the imagination. It appears that Tischbein employed a different tool to create the cave’s impenetrable darkness than the one used to create the fine lines that detail the lions’ fur, snake’s scales, and surrounding vegetation. The cave’s darkness, combined with the bare ground in the foreground and the rocky outcroppings that serve to frame the central figures, creates the impression of a stage. As though acknowledging the presence of possible spectators, the central male lion and snake both gaze out directly at the viewer. This not only brings the viewer into the drama but also raises the question of how we, as viewers, should interact with the piece. What is our role in the drama?

That being said, one of the print’s most notable features is its apparent lack of urgency. The central lion’s gaze is steady and calm despite the snake’s bite, which, the severity of which is clear from the blood dripping out of the wound. The snake also receives the lion’s bite, and gazes outward with equal equanimity. Unlike the Laocoön Group sculpture, where the father the father’s pain ripples to the surface and articulates itself in the beginnings of a scream, here Tischbein has leveled out and stilled the drama. It is as though the artist has frozen the scene before either the lion or snake can react. This suspension is troubling for the viewer, as it denies narrative progression and resolution. The only clue provided as to how the conflict will end lies to the left of the central lion, where a cub—whose position is reminiscent of that of the son to the left of the original sculpture—is crushed by the weight of the snake, with a hint of a scream suggested by the slight opening of its mouth.

Although prior knowledge of the Laocoön myth and sculpture is not necessary to be affected by the drama of Tischbein’s print, once this background has been explained the Tierlaokoon opens up to become a much more complex and potent work than expected. Tischbein’s deliberate quotation would have been legible to contemporary audiences and should be understood as part of an effort to engage with the aesthetic debates of his day. In summation, Tischbein’s Tierlaokoon is a stunning example of an artist’s innovative play with an established canon of pictorial and intellectual sources. While viewing Der Tierlaokoon I encourage you to not only think about its relationship to the wider context discussed this paper, but also to pay special attention to the print’s beauty and the skill that went into its creation. Although Tischbein is known primary for his paintings, he was also an incredible draftsman and printmaker. The line work and detailing on the vegetation, the detail of the snake’s scales, and softness of the lion’s mane is simply breathtaking. Viewed as a whole, the print offers the viewer a playground to explore and examine in detail. Situated in the larger context of this exhibition, the Tierlaokoon offers a small window in which one can view a fictionalized narrative and space that speaks to the earthly vision that Tischbein created.

—

[1] Different translations and versions of the myth result in confusion over what Laocoön did that offended the gods. However, the main consensus suggests that the god had forbidden Laocoön to have any children, but the priest went against the god’s wishes and had two sons. Another version suggests that during the Trojan war, the priest warned the Trojans about the deceit of the Trojan Horse and Athena was enraged thus sending the snake to kill Laocoön and his sons.

[2]https://www.museivaticani.va/content/museivaticani/en/collezioni/musei/museo-pio-clementino/Cortile-Ottagono/laocoonte.html

[3] See Sarah Blake McHam, Pliny and the Artistic Culture of the Italian Renaissance: The Legacy of the Natural History (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2013).

[4] Pliny the Elder, The Natural History, trans. John Bostock and Henry T. Riley (London: Henry G. Bohn, 2018), XXXVI: 36.4.

[5] Brilliant, Richard. My Laocoön: Alternative Claims in the Interpretation of Artworks. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2000. pp. 51. Also see Simon Richter, Laocoön’s Body and the Aesthetics of Pain: Winckelmann, Lessing, Herder, Moritz, Goethe (Detroit: Wayne State University Press, 1992); Alex Potts, Flesh and the Ideal: Winckelmann and the Origins of Art History. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994. pp. 68.

[6] Johann Joachim Winckelmann, “Gedanken über die Nachahmung der griechischen Werke in der Malerei und Bildhauerkunst,” in Kleine Schriften zum Geschichte der Kunst des Altertums (Leipzig: Insel-Verlag, 1925), 81.

[7] Johann Joachim Winckelmann, History of the Art of Antiquity, trans. Harry Francis Mallgrave (Los Angeles: Getty Research Institute, 2006), 206.

[8] Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Laocoon: An Essay on the Limits of Painting and Poetry, trans. Edward Allen McCormick (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 9-11.

[9] Ibid.,15-16.

[10] Ibid.

[11] William Guild Howard, “Goethe’s Essay Über Laokoon,” PMLA 21, no. 4 (1906): 934.

[12] Elaine P. Miller, “Goethe: The Metamorphosis of Plants,” The Vegetative Soul: From Philosophy of Nature to Subjectivity in the Feminine (Albany, NY: SUNY Press, 2002): 46.

[13] Ibid., 51.

[14] Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, “An Intermaxillary Bone is Present in the Upper Jaw of Man as well as in Animals,” in Goethe’s Collected Works, Volume 12: Scientific Studies, trans. Douglas Miller (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988).

[15] This title can be translated as “Different animal heads drawn after nature to give a more exact idea of their characters.”

[16] Franz Landsberger, Wilhelm Tischbein: Ein Künstlerleben des 18. Jahrhunderts (Leipzig: Klinkhardt und Biermann, 1908), 122-123. Also see Giulia Bartrum, German Romantic Prints and Drawings: From an English Private Collection (London: Contemporary Editions and the British Museum Press, 2011).

[17] Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbien, Aus meinem Leben (N.P.: Carl G.W. Schiller, 1861), 202-203.

[18] John F. Moffitt, “The Poet and the Painter: J. H. W. Tischbein’s ‘Perfect Portrait’ of Goethe in the Campagna (1786-87),” The Art Bulletin 65, no. 3 (1983): 440–55. Also see Bartrum, 122.

—

This site is for educational purposes only. Certain images on this website are protected by copyright and may be subject to other third party rights; downloading for commercial use is prohibited.