Displaced Mayflies: Ephemeral Ghostly Bodies in Yun-Fei Ji’s Three Gorges Dam Migration

Wenshu Wang

Chinese history flows along the Yellow and the Yangzi Rivers. Since the early days of Chinese civilization, these great waterways have served as key themes in philosophy, poetry, paintings, and literature. At the same time, taming the waters to prevent flooding has been a political task for Chinese leaders since the reign of Yu the Great (Da Yu) in Chinese legends.[1] The world’s largest hydroelectric project, the Three Gorges Project (Sanxia Gongcheng) was completed in 2006, almost a century after the idea was first proposed in 1919. While the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) celebrates the dam’s benefits in terms of irrigation, electricity supply, and water conservation, the work of the contemporary artist Yun-Fei Ji (b. 1963) explores the predicaments of displaced migrants. In The Three Gorges Dam Migration (fig. 1), a woodblock printed handscroll, Ji depicts an extended scene in which crowds of villagers with their baggage wait to move forward on their journey. Instead of offering a naturalistic depiction, Ji’s approach to his subject matter is imaginative and metaphorical. His handscroll not only visualizes the exhausting experience of displacement, but also reinforces its dehumanizing effect on the human body. Regarding the Three Gorges Dam migration as more than the relocation of people, Ji humanizes and historicizes this event by acknowledging the marginalized migrants in a monumental handscroll.

Fig. 1. Yun-Fei Ji, The Three Gorges Dam Migration. 2010, hand-printed watercolor woodblock mounted on paper and silk. Purchase, The Paul and Miriam Kirkley Fund for Acquisitions, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 2010.5.1. Image courtesy the artist and James Cohan, New York.

Yun-Fei Ji was born in Beijing and moved to the United States after earning his MAF degree from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. In 2002, Ji spent three weeks at the Three Gorges Dam areas including a large town near Wu Gorge and a town below White Emperor City as demolition began, taking many pictures that documented the built environment and situation of the migrants.[2] During Ji’s encounter with the migrants, he found that some of the names of their hometowns had already disappeared in the newer version of a map.[3] After his trip, Ji reoriented his artistic interest from historical memories to present experiences, and he created a series of ink paintings centered on the villagers who were forced to relocate, including The Empty City (2003), Water Rising (2006), and Last Day Before the Flood (2006). Continuing his ambition to memorialize the Three Gorges Dam migration, Ji’s collaborative work with the Rongbaozhai Studio (RBZ) in Beijing, The Three Gorges Dam Migration, has the most complicated making process and time investment. Ji created preliminary painted images, which he submitted to the artists at RBZ, who then created a reverse images of Ji’s paintings.[4] These reversed images were then passed on to woodblock to the studio’s carvers, who chiseled the image onto five hundred pear-wood blocks, which were then printed onto mulberry paper using a watery ink. After the printed sections were dried and flattened on hanging boards, the staff at RBZ attached them to backing paper using a thin wheat-starch paste, which was then mounted onto silk to create the twenty editions of the final handscroll.[5] What prompted Ji and his collaborators to devote so much time and energy to presenting the Three Gorges Dam migration on such a monumental scale?

As a symbol of China’s ambitious conquest of the waters, the Three Gorges Dam (Sanxia Daba) contributed to the political goal of picturing a modernized China to solidify the Chinese Communist Party’s regime. Spanning 193 miles (311 km), the Three Gorges comprises the Qutang, Wu, and Xiling gorges located at the middle reaches of the Yangzi River. As early as 1918, the first president of the Republic of China, Sun Yat-sen, published “The Fundamentals of National Reconstruction” and proposed constructing a dam at the downstream of the Three Gorges. Although the American government attempted to collaborate with the Chinese Nationalist Party (Guomindang) to launch the construction, the plan foundered due to the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937-1945) and the Chinese Civil War (1945-1949). After People’s Republic of China was founded in 1949, successive chairmen were conscious that damming the Yangzi River could demonstrate the new regime’s right to rule to the world. In 1994, the Three Gorges Dam project to construct a dam on the upper reaches of the Yangzi River was finally launched as a result of China’s economic and scientific development.

The success of the Three Gorges Dam project is inseparable from China’s ongoing transformation from an agricultural society to a socialist market economy, but it has also permanently reshaped local ecologies, topographic features, and social structures. The dam’s environmental effects include land inundation, soil erosion, water pollution, and a decrease in the land’s capacity to support human habitation.[6] Demolition and relocation were concurrent to dam construction. By the dam’s completion in 2012, more than 1.5 million rural residents were involuntarily relocated to other areas, and nearly 1,400 villages and towns were flooded.[7] Although these migrants were promised compensation, the process was marred by corruption and lack of transparency, so many of them were left without stable housing or income.[8]

Having personally witnessed the migration of people in the Badong area, Ji became concerned the relationship between hydroelectricity and modernization and intended to present the experience of displacement in a concrete visual form.[9] Ji’s scroll indexes the experience of displacement by generating visual exhaustion. To showcase the massive scale of this relocation, Ji framed the scene on a 32-foot-long handscroll. The scroll begins with four Chinese characters “Shui Zhang Ba Dong” (the water flooding in Badong) and articulates a narrative from right to left, according to the conventions of Chinese calligraphy. Traditionally, handscrolls are contemplated section by section. The reader would unroll the scroll by one hand and roll up it by the other hand to progress through its visual narrative. Although it is not permitted to handle the scroll in this way within a museum gallery, the viewer can nonetheless follow the migration process by walking along with the scroll from right to left when it is hung fully extended on the wall. In addition to the handscroll’s length, Ji’s depiction of the human body and compact composition also add to the overwhelming experience it provides the viewer.

Ji integrates the scroll’s human figures within the landscape through a consistent use of line, colors, and patterns to emphasize the intimate relationship linking migrants with the land. The overall landscape lacks a sense of depth and is densely packed with figures. In the middle section of the handscroll, trees, rocks, and clouds are overlapped with villagers of different ages engaged in a variety of quotidian activities. An old man smokes, while a young girl pulls her mother by the sleeve impatiently. People gather to converse in small groups and a female figure even sleeps on the ground amidst bundles of belongings. The contours of the human figures are rendered with discontinuous thin lines that lack firmness and stability, causing the human body to blend into the surrounding environment. Simultaneously, sacks of baggage are scattered and intermingle with twisted branches. The visual integrity and density of Ji’s approach to depiction reflects people’s deep-rooted attachment to their homeland, as though the migrants’ bodies and landscape form a single whole.

This visualization of the migrants’ deep attachment to the soon-to-be-flooded landscape is only one of the ways that Ji’s record of the Three Gorges Dam migration moves beyond naturalistic depiction. Another significant aspect of this move beyond the objective and empirical is Ji’s inclusion of fantastic and ghostly figures. Ji once said in an interview, “I wondered where all those ghosts would go when everyone had been relocated and imagined they would have to move too. I imagined how lonely it would be for them to be left behind.”[10] This concern with the spirits of the dead is reflected in Ji’s inclusion of silvery blue figures that seem to hover at the edge of visibility (Fig. 2 & Fig. 3). In China, the belief in ghosts can be traced back to the Six Dynasties Period (c. 220-589 C.E.). Ghosts were perceived as embodiments of the dead. It was widely believed that if a person received proper burial and sacrifice that the ghost of this person will not come back to harm innocent people.[11]

Fig. 2. Yun-Fei Ji, The Three Gorges Dam Migration, detail.

Fig. 3. Yun-Fei Ji, The Three Gorges Dam Migration, detail.

Anxiety would thus rise if a family member were not buried properly.[12] To ensure that the deceased rest in peace and bless their descendants, the ritual of ancestral worship is still widely operated by contemporary Chinese, especially those living in the countryside. Very few sources have discussed the relocation of graves during the resettlement process at the Three Gorges reservoir. The striking fact is that around 50,000 graves were relocated. Local residents excavated the coffins and skeletons to maintain the water’s quality and prevent not soaking their ancestors.[13] Since family kinship is deeply embedded in Chinese culture, the displaced still return to the edges of their former homeland to worship their ancestors, even though their ancestral graves no longer exist (Fig. 4).

Fig. 4. Villagers honouring ancestors, photographed by Li Feng. http://news.qz828.com/system/2014/11/28/010929407.shtml.

In addition to visualizing the relocation of ghosts, Ji’s scroll also explores the dehumanizing effect of involuntary displacement on the living migrants. Throughout the handscroll, the villagers are depicted as indifferent or preoccupied and barely make eye contact with the viewers. Their disengagement can be usefully contrasted with the frontality of the police officers who occupy a small watercraft to the far left of the scroll, overseeing the forced migration (Fig. 5). Despite the fact the migrants are overall moving toward the same direction (from right to left), they seem disoriented as the landscape ends at the shoreland. Many in fact face the opposite direction, as though reluctant to leave their homeland. In addition to this sense of loss and disorientation, Ji also included an anthropomorphic wild boar and other two semi-human figures wearing suits, whose heads resemble a fish or rock. (Fig. 6) These figures typify the more general instability of the human figure throughout the scroll, where bodies often seem on the verge of dissolving into the environment. Their migration resembles the flow of the Yangzi River, as though undertaken without full consciousness and certainly against their will.

Fig. 5. Yun-Fei Ji, The Three Gorges Dam Migration (detail).

Fig. 6. Yun-Fei Ji, The Three Gorges Dam Migration (detail).

To unpack the implication of these fluid bodies, it is necessary to contextualize the body in China’s pictorial history. Scholars of Chinese art history have argued that Chinese pictorial tradition approaches the body as ontologically dispersed rather than objective because it is a systematic framework for experience, not a clearly defined object. According to John Hay, the objectified and “solid” nude body is absent in Chinese paintings. Instead, “the body was dispersed through metaphors, locating it in the natural world by transformational resonance and brushwork that embodied the cosmic-human reality of qi, or energy.”[14] With this in mind, the natural landscape depicted in Ji’s scroll, with its bamboos, plants, and trees, can be seen as the embodiments of the body both visually and metaphorically. For instance, consider the two female figures bowing their heads towards the ground. The branches next to them are bent and twisted to echo the poses of the women (Fig. 7). The disturbing and chaotic elements of the landscape thus incarnate the experience of the displaced peoples. Both the land and migrants face the same fate of disruption and forced removal.

Fig. 7. Yun-Fei Ji, The Three Gorges Dam Migration (detail).

Moreover, Ji’s portrayal of the female body visualizes the migrants’ degraded predicaments. Garments signify one’s social class and identity both in Western and Chinese paintings, and in Ji’s scroll many figures are shabbily dressed in wrinkled clothing and some are even in states of partial undress. This is significant because in the Chinese pictorial tradition, nudity is also generally restricted to pornographic paintings.[15] Consider, for instance, the female figure sleeping on the ground in the middle section of the scroll (fig.8), which is posed similarly to the female nude in the French painter Pierre-Auguste Renoir’s Reclining Nude (figs. 9-8). Renoir depicts a sleeping young woman from behind, whose body is surrounded by soft grass and a blanket that partially covers her thighs. Although the nude’s identity is unknown, Renoir romanticizes and idealizes the nude by stressing her bodily curves, wrinkle-free skin, silky hair, and plump breasts. The female model’s absent face and uncertain identity evoke the curiosity of the male viewers and leave them a space for imagination. In contrast, the reclining body in Ji’s print is half-naked since her arm, legs, and waist are exposed to the air. Sleeping in an open space, she lies on the hard ground between a wheelbarrow and rambling trees. Her nakedness, however, does not serve as a sexual attraction but instead accentuates her degradation as she is exposed to anyone who might happen by, as well as the viewer’s gaze. The visual comparison between Ji and Renoir’s artworks reflects the female villager’s lost privacy and dignity.

Fig. 8. Yun-Fei Ji, The Three Gorges Dam Migration (detail).

Fig. 9. Pierre-Auguste Renoir (French, 1841-1919), Reclining Nude. 1892, Oil on canvas, 13 x 16 3/8 in. (33.0 x 41.5 cm). Norton Simon Art Foundation.

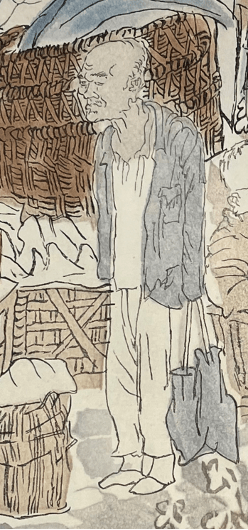

Another relevant comparison to Ji’s scroll is its reference to liumin tu (images of refugees). By associating the Three Gorges Dam migrants with ghosts, Ji implies their fragmented identity and marginalized social status caused by the displacement. In doing so, he drew on a longer tradition within Chinese scroll painting. As Alice Bianchi notes, “in China, beggars and other marginal and displaced figures with no clear social place or identity have long been associated with ghosts and demons.”[16] Ji applies this pictorial tradition as a strategy to picture the suffering caused by the experience of displacement. Zhou Chen’s Beggars and Street Characters (fig.10) from the Ming Dynasty exemplifies liumin tu with a series of figurative portraits of distressed beggars. When placed alongside Ji’s scroll, we can observe visual similarities between Zhou and Ji’s figures in terms of their hunchback, anxious facial expression, wrinkled garments, and generally undignified appearance (fig. 11-12). By obscuring the boundary between the living and the dead, the portrayals of the migrants convey an uncanny and disturbing feeling to the viewers.

Fig. 10. Zhou Chen (Chinese, c. 1450-c. 1536), Beggars and Street Characters. 1516, handscroll, ink and light color on paper, 31.9 x 244.5 cm (12 9/16 x 96 1/4 in.). The Cleveland Museum of Art, John L. Severance Fund. 1964.94.

Fig. 11. Yun-Fei Ji, The Three Gorges Dam Migration (detail).

Fig. 12. Zhou Chen, Beggars and Street Characters (detail).

Ji’s critical interpretation of the Three Gorges Dam migration is manifested not only in his depiction of the migrants and the landscape, but also in his approach to the handscroll as a format. The handscroll is the most common-used format for traditional landscape painting in China. Chinese government has promoted the monumentality of the ancient ink painting as a testament to China’s glorious history, which at the same time serves to legitimate the Chinese Communist Party within a longer lineage of leaders. Sharing a similar motif of Ji’s scroll, the spectacular landscape painting, Wu Wei’s Ten Thousand Miles on the Yangzi River (fig. 13) features the scenery along the Yangzi River with continuous mountains and flowing waters. Wu Wei’s painting is known as literati painting (wenren hua) that demonstrates the artist’s “intellectual achievement and moral integrity.”[17] The humans are invisible in Wu Wei’s painting because it suggests the poetic effect and favors a calligraphical ideology in which the waters and mountains are painted in abstract forms and a simplified composition.[18] However, the landscape in Ji’s work is sprawling and most of the space is occupied by the villagers. Ji’s choice of expanding the resettlement story on this magnificent format does not aim to undermine the ancient medium, nor to convey a direct critique to the central government. Rather, he reminds the viewers that the reshaped land in the contemporary era has an inherent history that archives people’s memory of struggling and contributing. Even though the land has transformed from literati’s high-minded contemplation to exploitive resources, the imprints of preceding events remain and can be traced by different methods.

Fig. 13. Wu Wei (Chinese, c.1459-1508), Ten Thousand Miles on the Yangzi River (detail). 1506, ink and light colors on silk, 27.8 x 976.2 cm. Palace Museum, Beijing.

Ji acknowledges the hardship that migrants have undergone to historize this moment from a humanistic perspective. To the average person unfamiliar with the experience of the migration, the impact of the Three Gorges Dam might be represented in the quantifiable number of relocated people. Ji’s handscroll, however, reminds us that the displaced had to give up more than their homes and livelihoods. The construction of the dam forced residents of the area to leave behind their ancestors and the homelands in which their families had lived for generations. They also lost the sense of belonging that comes with such rooted attachments and faced marginalization in new and provisional shelters. The precarity depicted in Ji’s scroll recalls the lines that the Song Dynasty scholar Su Shi included in his First Ode on the Red Cliffs (Qian Chibifu): “We are like mayflies wandering in this terrestrial world or a grain of millet drifting on a deep ocean. What a short life span we have, yet how endless the Yangtze River is.”[19] Although the Yangzi River, despite human interventions, remains, the migrants depicted in Ji’s scroll evoke Su’s anonymous mayflies disappearing in the long river of history eventually.

It was perhaps in an effort to prevent this disappearance that Ji devoted such considerable efforts to producing the Migrants of the Three Gorges Dam to draw attention to and memorialize the collective experience of displacement, which has had long-term effects on migrants. Ten years after being relocated from the province of Guangdong in 2001, a migrant from Chongqing was interviewed by a journalist about his experience. According to the journalist, the migrant explained that “assimilating into the local communities is not as easy as changing one’s eating habits, and migrants of his generation make sacrifices only for their children because it would take him a couple more decades to become a local.”[20] To prevent the traumatic resettlement of marginalized villagers from sinking into oblivion, Ji created a visual record that does not simply document but internalizes the experience of the displaced in formal terms. Memorializing the difficulties undergone by the migrants, Ji’s scroll stands as a monument to the human story of displacement behind the construction of the world’s largest hydroelectric dam.

—

[1] Yu the Great spent thirteen years to conquer the Yellow River, and his selfless spirit for his career has inspired successive Chinese leaders.

[2] Wu Hung, “A Conversation Between Yun-Fei Ji and Wu Hung,” in Displacement: The Three Gorges Dam and Contemporary Chinese Art (Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, 2008), 104.

[3] Ibid.

[4] Rongbaozhai, Yun-Fei Ji and May Castleberry, “Interview with Artists from Rongbaozhai,” Art Journal 69, no. 3 (Fall 2010): 79.

[5] Katy Siegel and June Y. Mei, “Yun-Fei Ji’s Three Gorges Dam Migration,” Art Journal 69, no. 3 (Fall 2010): 77.

[6] Yan Tan and Fajun Yao, “Three Gorges Project: Effects of Resettlement on the Environment in the Reservoir Area and Countermeasures,” Population and Environment 27, no. 4 (Mar. 2006): 368.

[7] Wu Hung, “Internalizing Displacement: The Three Gorges Dam and Contemporary Chinese Art,” in Displacement: The Three Gorges Dam and Contemporary Chinese Art (Chicago: Smart Museum of Art, 2008), 13.

[8] Alice Tianbo Zhang, “Within but Without: Involuntary Displacement and Economic Development” (PhD Diss., Columbia University, 2018), 10.

[9] Wu Hung, “A Conversation Between Yun-Fei Ji and Wu Hung,” 104.

[10] Lilly Wei, “Yun-Fei Ji: ‘I’m Pessimistic about China,’” Studio International, accessed by December 10, 2021, https://www.studiointernational.com/index.php/yun-fei-ji-interview.

[11] Mu-chou Poo, “The Culture of Ghosts in The Six Dynasties Period (c. 220-589 C.E.),” in Rethinking Ghosts in World Religions, ed. Mu-chou Poo (Leiden; Boston: Brill, 2009), 245.

[12] Ibid.

[13] Yi Hongwei and Gao Li, “Focus on the Relocation of Graves in the Three Gorges,” last modified September 4, 2002, https://news.sina.com.cn/c/2002-09-04/1358706207.html.

[14] John Hay, “The Body Invisible in Chinese Art?” in Body, Subject & Power in China, ed. Angela Zito and Tani E. Barlow (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1994), 42.

[15] Ibid, 44.

[16] Alice Bianchi, “Ghost-Like Beggars in Chinese Painting: The Case of Zhou Chen,” in fantômes dans l’extrême-orient d’hier et d’aujourd’hui – tome1, ed. Marie Laureillard and Vincent Durand-Dastès (Paris: Presses de l’Inalco, 2017), 225.

[17] Kim Karlsson and Alexandra von Przychowski, Longing for Nature: Reading Landscapes in Chinese Art (Zürich: Museum Rietberg, 2020), 11.

[18] Ibid.

[19] The original text: 寄蜉蝣於天地, 渺滄海之一粟. 哀吾生之須臾, 羨長江之無窮.

[20] Xu Weiming, “Ten Years of the Three Gorges Dam Migration,” last modified August 22, 2011, https://news.qq.com/a/20110820/000706.htm.

—

This site is for educational purposes only. Certain images on this website are protected by copyright and may be subject to other third party rights; downloading for commercial use is prohibited.