H. C. Westermann’s Precarious Landscapes

Sabrina Cunningham

Born in Los Angeles in 1922, H.C. Westermann accumulated a rare depth and breadth of experience before beginning his artistic practice in earnest during the 1950s. This personal history, which included serving in two wars, is expressed consistently throughout his body of work, with varying degrees of clarity and directness. Although Westermann is primarily recognized for his sculptural works, he was also a prolific illustrator throughout his life and created several series of prints. In the mid-1970s, he created “The Connecticut Ballroom” suite, a series of seven woodcut prints made entirely in his home studio in Connecticut. In this essay, I consider two of these prints, Arctic Death Ship (1976) and Deserted Airport N.M. (1975-76), in relation to Westermann’s practice and sociopolitical context as a professional artist. Not only do these two works of art demonstrate a prime example of his social, ecological, and existential concerns, but also offer a more subtle glimpse at his guiding convictions.

At the age of twenty, Westermann, after having been raised in Los Angeles for the whole of his life, acquired a job as a rail worker in the logging camps of the Pacific Northwest.[1] Although Westermann only spent seven months as a ‘gandy dancer’ before he enlisted as a Marine in July 1942, his time in the logging industry can be considered the beginning of a lifelong manual, working relationship with wood.[2] Over the next three years, he served as an anti-aircraft gunner aboard the USS Enterprise. Although Westermann’s decision to enlist was driven by a patriotic sense of heroic duty, the veneer of adventure was soon wiped away as “the full horror of the war was brought home and it became a real nightmare” for Westermann as he witnessed kamikaze aerial attacks, the destruction of entire warships, and an ever-present lethality embodied by the “smell of death” he described as emanating from dead sailors’ bodies.[3] His experience of violence during World War II saturates his whole body of work, which often communicates an atmosphere of pervasive danger. In 1946, having returned home after the end of the war, he briefly toured East Asia as one half of a gymnastic performance act sponsored by the United Service Organization (USO), before returning to the United States once again to attend the School of the Art Institute of Chicago from 1947 to 1950.

Westermann’s time at the Art Institute was interrupted in 1951, when he enlisted and served in the Korean War.[4] While such a course of action was common for veterans of World War II, this period of conflict “finally soured him on the efficacy of combat,” and he returned from Korea after only a year.[5] After completing his education at the Art Institute in 1954, he began his professional practice in Chicago’s art scene in the midst of a burgeoning Cold War.[6] While removed from the visceral mortality that would have been present on the battlefield, Westermann’s experiences indelibly opened his eyes to a level of worldwide precarity that had not existed before the war, epitomized by the massive scale at which death could be inflicted in the form of the atomic bomb. David McCarthy described the expression of these existential threats in Westermann’s work as “a metaphor of human powerlessness before overwhelming forces and a framing element chosen to bring into view this hostile world.”[7] Yet despite, or perhaps because of, the macabre nature of his subject matter, there is a persistent sense of humor in his works. His sculptural, illustrated, and printed works are full of instances of his affinity for verbal and visual puns, paradoxes, and demonstrate his “[involvement] with the conceptually absurd.”[8] This tragicomic leaning has led several art critics to identify his practice with the work of the ‘Monster Roster’ (a group of Chicago-based artists who attended the School of the Art Institute at the same time as Westermann) in that his work serves as an example of the ‘grotesque.’ Kozloff, in particular, identifies Westermann’s version of the grotesque as emblematic of Baudelaire’s “concept of the ‘absolute comic,’ which induces a profound laughter when, ironically, fallen humanity claims its superiority to nature.”[9]

Fig. 1. H. C. Westermann, See America First: Untitled #2. 1968, four-color lithograph on German Etching paper with torn and deckled edges. The H.C. Westermann Study Collection, Gift of the Estate of Joanna Beall Westermann, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 2002.212.

In addition to his sense of black humor, Westermann’s works are deeply marked by his experiences of travel. One key moment in his practice occurred during a cross-country road trip to San Francisco that he undertook which his wife, Joanna, in 1964; during the year thereafter the couple lived in the Bay Area, Westermann produced a number of sculptures and illustrations that formed the basis of the “Death Ship” motif that proliferates his work.[10] This trip, during which Westermann and Joanna lived and traveled via a truck that Westermann retrofitted himself, served as the basis for his See America First suite of prints (fig. 1).[11] The title suggests the “See America First” campaign of the early- to mid-twentieth century to promote domestic tourism. Subverting the subject matter of tourism industry’s postcards and posters, Westermann’s prints feature surreal and imagined landscapes, ‘Wild West’ panoramas, Death Ships surrounded by threatening marine life, and the placement of comical and strange humanoid figures within these scenes. While Westermann, who was famously reticent when discussing his work, may not have characterized these prints as engaging in social or political critique, the series seems to express a simultaneous cynicism and fascination towards the America it depicts. It offers, if not a critique exactly, at least a backhanded compliment.

Westermann was also noted for being an avid consumer of science fiction media, especially “films that underscored the potential disaster resulting from the nuclear proliferation of the Cold War.”[12] For those living during the height of the Cold War, the threat of total annihilation would have been a viscerally real one, as technoscientific advancement enabled the possibility of a global thermonuclear war that could potentially eliminate life on earth.[13] A preference for the genre of science fiction is extremely fitting for Westermann. As Amy Butt has argued, science fiction can be regarded as “a genre of cognitive estrangement” and “a critical design tool which allows us to reflect on the world we inhabit.”[14] Many of Westermann’s prints depict alien landscapes, extraterrestrial aerial attacks on urban centers, and scenes of decay implicating a post-human reclamation of buildings by nature. Although artificial, the scenes that Westermann crafts utilize familiar locales and tropes to superimpose speculative futures over present. The critical power in these prints lies not in any sort of explicit moralizing, but in how they manage to paradoxically draw attention to the present by first directing it to a fictitious one. The generative tension between (technological, scientific) reality and fiction, manifested most popularly in the science fiction genre, is also decidedly present in Westermann’s “The Connecticut Ballroom” suite of prints.

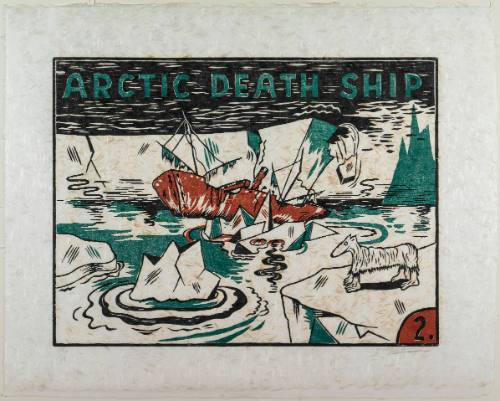

Fig. 2. H. C. Westermann, Arctic Death Ship, from the portfolio: The Connecticut Ballroom. 1975, three-color woodcut on Natsume wove paper. The H. C. Westermann Study Collection, Gift of the Estate of Joanna Beall Westermann, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 2002.238.

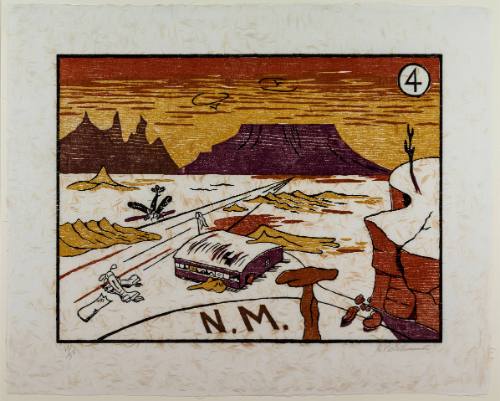

“The Connecticut Ballroom” suite, created towards the end of Westermann’s life during the mid 1970s, was the first group of his printed works to be created entirely by the artist at his home studio in Connecticut. Each of the seven works are woodcut prints, and are the result of extensive planning, experimentation, and notetaking by Westermann. While Westermann’s devotion to craftsmanship and detail is readily apparent in his sculptural works, a print can often belie the complex and time-consuming process behind the final image. This series of woodcuts, and the accompanying plethora of test blocks, sketches, and notes that went into their production demonstrate “the artist’s thorough-going concern in all his works, whatever the medium, with solid technical processes and mastery of them through careful research and testing.”[15] The subject matter of this series also represents Westermann’s turn away from the outright depiction of warfare to more assertively address his “environmental concerns and what he saw as the destruction of Earth’s natural energy and resources,” which had begun during the creation of his “See America First” series.[16] The world depicted in “The Connecticut Ballroom” speaks to an understanding of the increasing fragility of human life and the natural world following the expansion of consumerism, progress narratives, and modern science during the preceding decade. Arctic Death Ship (fig. 2) and Deserted Airport N.M. (fig. 3) stand out from the rest of the series as the only two landscapes devoid of human figures and any sign of life save for a ratty polar bear, a spindly tree, and the faint outlines of desert vultures. The lack of human subjects is emphasized by the presence of the structures left behind, prompting the viewer to wonder at their absence.

Fig. 3. H. C. Westermann, Deserted Airport N.M., from the portfolio: The Connecticut Ballroom. 1975, four-color woodcut on Natsume wove paper. The H. C. Westermann Study Collection, Gift of the Estate of Joanna Beall Westermann, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 2002.241.

The subject matter of Arctic Death Ship recalls a similar print from “See America First,” Untitled #16, in which the Death Ship is trapped in pack ice, surrounded by steep glaciers and similarly accompanied by a polar bear. However, the ship of Arctic Death Ship appears more immediately threatened by the forces of the frozen north, where chunks of crumbling icebergs seem to pierce an already-sinking vessel as the polar bear looks on. In this scene, the ship takes on a transitional, or liminal, quality: has the ship been abandoned as her sailors watch from the same safe vantagepoint as the viewer, or do they remain inside their vessel and soon-to-be-tomb? McCarthy succinctly elaborates on this subtext by observing that “the ship conceived as coffin provided Westermann with a simple, yet highly-charged metaphor of human vulnerability that had roots in romantic art and literature.”[17] This print’s connection to Romantic art, whether intended by Westermann or not, can be detected in its striking resemblance to the Romantic painter Caspar David Friedrich’s Das Eismeer (1823-24). Friendrich’s painting foregrounds a towering mountain of ice overtaking a nearly-buried ship, while Westermann’s print presents the ship as its central subject. However, both works present the ship—a symbol of human vulnerability—as fatally subject to powerful forces beyond human control.

A similar reading can be made of Westermann’s Deserted Airport N.M., which depicts the decaying remains of two aircraft and hangar in the process of being swallowed by a sweeping desert vista. The title is reflective of Westermann’s adept hold on language and his particular brand of humor: the absence of human figures and state of disrepair suggests its desertion, while the mounds of sand encroaching on the runway and hangar imply the airport’s re-desertification. The only signs of life are the vultures circling over the empty landscape and a spindly tree of questionable vitality. This print offers another glimpse into Westermann’s interest in science fictional depictions of post-nuclear worlds. Depopulated and punctuated by aircraft left to rot where they crashed, the work presents a post-apocalyptic world in which the desert reclaims and reincorporates the last remaining signs of human activity. Like the science fiction genre, Westermann’s desert landscape presents a speculative future by superimposing it onto the present. The effect is especially potent given its setting in New Mexico, where the nuclear bomb was invented and tested for decades. Considered in conversation with Arctic Death Ship, this pair of landscapes points to a central paradox in the technoscientific discourse of its moment: that a hubris about the imperviousness of human society to nature’s forces existed alongside the real threat of human-induced environmental destruction.

Throughout his oeuvre and with this pair of works in particular, Westermann consistently confronts the viewer with a reality that they might otherwise prefer to pretend isn’t there. His way of seeing the world was unmistakably a product of the postwar era, which revealed a newly hostile and fragile world that was “absurd, harsh, and without redemptive features other than the sincerity of personal relationships, heroism, and a nobility of character.”[18] The prevalence of destruction, degradation, poisoning, and decomposition in “The Connecticut Ballroom” suite pushes back against the anesthetic narrative of perpetual progress and improvement delivered by modern science’s incorporation into everyday life, reminding the viewer of the world-ending capacity of that same science. However, Westermann’s harsh realities do not convey despair or defeat that one might expect from such subject matter, but rather seem to issue an invitation to confront those realities head-on. Westermann valued above all else “personal integrity…[the] ability to face things as they [are], [to be] decent…and not just run away from everything. Courage…physical courage, and other types of courage.”[19] The precarity of local and planetary environments is something that we, as contemporary viewers, have become intimately familiar with as we begin to experience the effects of climate change around the world. Corporate pollution, governmental inaction, and the humanitarian crises resultant from human-driven environmental disasters seem insurmountable, at least by individual efforts. Perhaps, in the looming shadow of the climate crisis, Westermann’s values and the body of work in which these values are suffused can serve as a model of how to courageously look a frightening reality directly in the eye.

—

[1] Beatriz Velasquez et al., H. C. Westermann: Goin’ Home (Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofia, 2019), 55.

[2] David McCarthy, H.C. Westermann At War: Art and Manhood in Cold War America (Newark : Cranbury, NJ: University of Delaware Press ; Associated University Presses, 2004), 25.

[3] Velasquez et al., 156.

[4] Ibid., 158.

[5] McCarthy, 62.

[6] Dennis Adrian, See America First: The Prints of H. C. Westermann (Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, University of Chicago, 2001), 32.

[7] McCarthy, 77.

[8] Velasquez et al., 27.

[9] McCarthy, 55.

[10]McCarthy, 113.

[11] Adrian, 69.

[12] Adrian, 60.

[13] M. Jimmie Killingsworth and Jaqueline S. Palmer, Nuclear New Mexico: A Historical, Natural, and Virtual Tour (College Station: Texas A & M University Press, 2018), 1.

[14] Amy Butt, “The Present as Past: Science Fiction and the Museum,” Open Library of the Humanities 7, no. 1 (2021): 3.

[15] Adrian, 171.

[16] Adrian, 74.

[17] McCarthy, 19.

[18] Velasquez et al., 29.

[19] Westermann quoted in McCarthy, 29.

—

This site is for educational purposes only. Certain images on this website are protected by copyright and may be subject to other third party rights; downloading for commercial use is prohibited.