The Culture of Nature and The Nature of Culture: On Mark Dion’s Roundup: An Entomological Endeavor for the Smart Museum

Datura Zhou

The Flâneur and The Nature

To be away from home and yet to feel oneself everywhere at home; to see the world, to be at the center of the world, and yet to remain hidden from the world… The spectator is a prince who everywhere rejoices in his incognito. The lover of life makes the whole world his family.

— Charles Baudelaire[1]

Should we not learn the lesson that, for example, the woods, which poets praise as the human being’s loveliest abode, is hardly grasped in its true meaning if we relate it only to ourselves?… The meaning of the forest is multiplied a thousandfold if one does not limit oneself to its relations to human subjects but also includes animals.

— Jakob von Uexküll[2]

The flâneur was defined in Charles Baudelaire’s essay, “The Painter of Modern Life,” as “the lover of life” strolling through the city streets. The flâneur (or flâneuse) may be characterized as a leisurely pedestrian, unencumbered by any obligation or sense of urgency, but embodied the ideal of a modern city dweller with a keen awareness of his or her surroundings. Urban life compels most of us to get lost in a variety of noises and places. However, a certain practice of attention is required to listen to the voice of the world.[3] Although originally articulated in the 1860s, the idea of the flaneur has also served as a model for artistic engagement that draws upon the vital energy of daily life, even as artists have interrogated the way gender, race, and class underlay Baudelaire’s original model. The idea of contemporary artists engaging the city with the sensibility of a flâneur suggests a heightened awareness of the urban environment and phenomena within it, and therefore presents novel possibilities for participating and intervening in culture, challenging expectations and opening up new ways of perceiving.[4]

The idea of the flâneur suggests the act of wandering in the city could be the initiation of artmaking. Quite often, we slip through the city without acknowledging the nonhuman lives that are everywhere around us. Therefore, the art of looking for what is not easy to see has the potential to transform our everyday experiences of the world around us, prompting us to attend to the ever-present but unfamiliar. As the conceptual artist Mark Dion argues, “the job of the artist is to go against the grain of dominant culture, to challenge perception and convention.” His installation, Roundup: An Entomological Endeavor for the Smart Museum of Art (fig. 1), can be understood as contributing to this goal by encouraging viewers to consider the tiny insects that share the space of the museum with art objects, gallery visitors, and museum staff. Looking at the grid of microscopic photographs hung beyond the mannequin that stands in for the artist, one has the impression of almost hearing the inaudible keening of a tiny bugs who make their home in the museum’s walls and crevices, challenging our human-centered perception of the world.

Fig. 1. Mark Dion, Roundup: An Entomological Endeavor for the Smart Museum of Art. 2000/2006, mixed media installation of black-and-white photographs and mannequin. Purchase, Paul and Miriam Kirkley Fund for Acquisitions, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago, 2007.107a-c.

In what ways does looking for insects lead us to appreciate the fuller complexity of built environment? Insects, along with spiders and crustaceans, belong to the arthropod category, the largest animal phylum. Insects can be ubiquitous and difficult to discern because their diminutive size strains human beings’ usual limits of attention. They have been excluded from the cultural production of knowledge because of an anthropocentric perspective that renders them invisible or reduced them to ciphers for human meanings. To counter the anthropocentrism of the biological sciences, the early twentieth-century German biologist Jakob von Uexküll introduced the concept of Umwelt, a German word for the environment that Uexküll employed to describe the unique sensory world that inhabited by each individual organism (in contrast to that inhabited by any other). Uexküll has argued that “every animal, no matter how free in its movements, is bound to its own customized dwelling world.”[5] Thus, there is no one unified objective world but many subjective worlds. All subjects are inclined to see the world as though it existed only for them – humans see the world anthropocentrically; alternatively, squirrels see the world squirrel-centrically. According to Uexkull, it was the job of the ecologist to investigate the limits of these worlds, and it is striking that he employed a notion of the “stroll” that echoes the concept of flânerie.[6] Yet although it is tempting to compare the scientist and flaneur, it is perhaps the insects that embody Baudelaire’s notion of a subject that “see[s] the world, [is] at the center of the world, and yet remain[s] hidden from the world. As the artist and curator Andrew Yang has argued, Baudelaire could just as well be describing insects, so ubiquitous and invisible in the urban environment.[7]

Roundup: An Entomological Endeavor for the Smart Museum

There is something revealing in the awkwardness in our thinking about nature and particularly in our articulation of the difference that separates Homo sapiens from other living creatures. Our notion of nature as something separate, as something ‘out there’ tethered to the idea of wilderness, remains one of the prevalent and pernicious urban prejudices. Nature seems not to be found in the everyday unless magnified. By shifting our focus, we can be reminded that we are inalienably part of an ecology—we are constructed by and construct the world around us. My project for the Smart Museum is a modest attempt to re-tie severed bonds with the non-human world by negotiating a space of encounter.

— Mark Dion[8]

Summer brings sweltering heat to the American Midwest, and Chicago especially becomes its own tropical microcosm. Unlike humans who seek out climactic consistency, animals – like arthropods – thrive amidst the tropical humidity. Mark Dion’s Roundup: An Entomological Endeavor for the Smart Museum, which began as an interactive performance and ended in the form of an installation, adopts these animals as a fitting subject. The work originated as a commission for the Smart Museum’s exhibition Ecologies: Mark Dion, Peter Fend, Dan Peterman, which was curated by Stephanie Smith in 2000. The work began as a performance in which the artist led a team of volunteers, including fellow artists, museum staff, faculty, and students to collect insects from the crevices of the Smart Museum. Dion then set up a temporary lab within the Gray Gallery in which he worked alongside a University of Chicago microscopist to create photographic “portraits” of the dried specimens, which we see on display in the final installation.

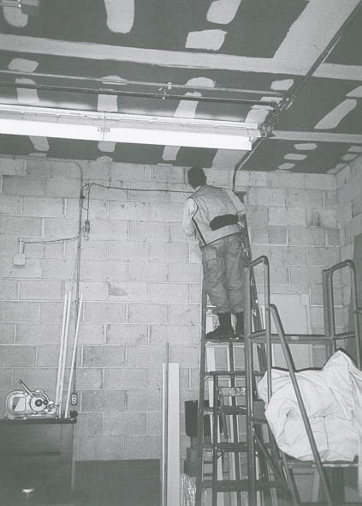

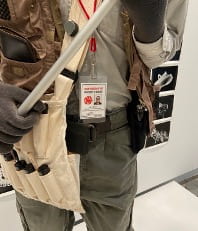

With an edge of irony and humor, Mark Dion’s work adapts and deconstructs scientific and museum-based rituals of collecting and exhibiting objects. Roundup is as much a work of science as it is a work of art. As the creative director and a participant of the project, Dion put on a naturalist’s costume—tan cargo pants, a light grey button-down shirt, well-worn leather boots, a canvas vest, and his trademark black-framed glasses (fig. 2)—and led a group of volunteers, including scholars, curators, and artists, in a bug hunt throughout the building, from the loading dock to the director’s office (fig. 3-5).[9] After the collecting process, he changed into a dark lab coat to analyze the culled arthropods in the small temporary laboratory constructed in the Smart Museum’s galleries, which included a high-tech Stemi 2000-C Zeiss stereo microscope, which could enlarge specimens invisible to the naked eye (fig. 6). He then photographed the specimens, producing the pictures included in the final installation.[10]

Fig. 2. Mark Dion, Roundup: An Entomological Endeavor for the Smart Museum. Installation details. SAIC Galleries, The School of Art Institute of Chicago. Photo taken by Datura Zhou in October 2021.

Figs. 3-5. Dion and his Team Collecting Arthropod Specimens in the Smart Museum of Art, July 2000. Photos reproduced in Stephanie Smith, Ecologies: Mark Dion, Peter Fend, Dan Peterman (Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, 2001).

The mannequin standing on the platform in this final manifestation of the work presents Dion in the style of a tropical entomologist. The clothes that he wears, the magnifying glass and several test tubes in his pockets, the butterfly net in hand, and the Smart Museum Staff ID Card hanging at his waist all provide a degree of legitimacy to the work of science as art (fig. 7). And yet these clothes could also read as costumes. When looking at Dion’s installation, the audience is immediately attracted by the mannequin, but one can only wonder if the performance to which it refers was a matter of fact or fiction, as the definition of clothes and props, in this case, intertwine.[11] Moreover, Dion seems to be exploiting the potential humor of his get-up for theatrical effect. One might wonder, for instance, how useful the butterfly net would be when it comes to catching the crawling insects pictured in the photographs that hang behind the mannequin. As Stephanie Smith noted in her discussion of Dion’s work, the entire entomological endeavor “mingled research and performance.”[12] Dion’s role shifts between the artist and the scientist.

Fig. 6. Dion and University of Chicago Microscopist Allan Lesage examine, organize and photograph insects in Mark Dion’s Laboratory, July 2000. Photo reproduced in Stephanie Smith, Ecologies.

Fig. 7. Mark Dion, Roundup: An Entomological Endeavor for the Smart Museum. Mannequin details. SAIC Galleries, The School of Art Institute of Chicago. Photo taken by Datura Zhou in October 2021.

In addition to the mannequin, Dion’s arthropod art takes the viewers beyond the display of the collected and transforms the specimens into artful portraits. These entomological portraits are enlarged microscopic images of different specimens that glow in translucent white against a black background with a white border. As Smith writes:

“These images approached portraiture, not in any traditional sense of likeness of psychological acuity, but by virtue of the individuality imparted to each newly dead or long-desiccated insect through manipulations of pose or lighting. The choice to highlight the insects against dark, dust-flecked grounds also monumentalized them within almost stellar fields, a visual link between micro- and macrocosm.”[13]

Dion’s bug portraits bring the bodies of insects into the foreground in a space typically occupied by works of art, highlighting a part of the urban environment that is often overlooked and considered insignificant, encouraging the viewer to consider the interrelation of the natural and human world. Furthermore, creatures of this type are routinely destroyed by herbicides like Roundup, the source of Dion’s title, which points to the human’s destructive attempts to control nature and its nonhuman inhabitants.

Dion’s “entomological endeavor” interrogates longstanding paradigms of classification and categorization. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, the production of knowledge in natural history involved collecting, classifying, and preserving insects. Alissa Mazow has argued that Dion’s exploration of these bugs has proven to be central to his study of cultural constructions of order and knowledge. The artist effectively bridges the art-science divide, bringing together style and morphology, artist and science, the art and nature. Through the display of his bug portraits, Dion heightens our experiences with the insects and provides us a visual data set of scientific evidence but in an artistic artifact of formats. This effect is heightened by the fact that, viewers cannot easily identify the “portraits” with specific insects since the specimens are not labelled.

Additionally, Mazow has claimed that the format of the bug photographs suggests not only portraits, but the evidence of a crime scene. As she puts, “the modernist grids of bugs recall the arrangement of ‘fugitive’ portraits in Andy Warhol’s Thirteen Most Wanted Men (1964) in addition to their similar use of both photography and a black and white color scheme.”[14] While Warhol’s photograph, as the art historian Richard Meyer has argued, challenged social values of sexual orientation and desire, Dion’s bug portraits confront the issue of classification and identification.[15] Like Warhol’s “criminals,” Dion’s arthropods either gaze at each other or face out at the viewer, conveying the unnaturalness of this monumental and yet intimate form of display. As Mazow argues,

“By blowing up the bugs, Dion forces his arthropods to escape taxonomical boundaries. Thus, as the organisms momentarily leave the corporeality of their bodies, they display themselves as patterns of lines and shapes, and less clearly as examples of specific species than as specific objects.”[16]

By any empirical measure, insects are at “the center of the world,” as Baudelaire put it. There is an estimate of 10 quintillion insects on Earth – That’s about 1.5 billion insects for every person on the planet. By weight, it’s about 300 pounds of them for every pound of us.[17] Regardless, bugs are near the bottom of our zoological pyramid, in which humans are at the top. The study of insects, therefore, proves particularly relevant in demonstrating the inequities underlying our hierarchical classification system as well as in our broader hierarchical cultural systems. In relation to Warhol’s subjects, Dion’s Roundup project reminds us how different and yet similar we are to arthropod animals in the greater cosmological vision. The viewers are challenged to reconsider the hierarchy of nature and culture, as well as to revisit our consciousness that places humans in a position above all other beings.

Dioramas and Natural History

Recreating a three-dimensional scene frozen in time and space, the diorama is usually enclosed in a display case, composed of a painted backdrop, props and figures… Although the etymology of diorama means “to see through”, the device also stands as a screen onto which a world of fantasy and fiction merges with the display of knowledge and science.

— Dioramas (Palais de Tokyo, 2017)

Art and natural history have historically come together in two modes of display: the cabinet of curiosity and the diorama. Cabinets of curiosities, also known as “wonder rooms,” are collections of notable objects and artifacts and are often regarded as a precursor to the modern art museum. Dioramas are constructed and staged scenes that can include a mix of preserved natural specimens and artificial models and are often found in natural history museums. Dioramas provided dramatized displays to maximize engagement.[18] Unlike the idiosyncratic tone of the cabinets of curiosities, dioramas often narrate universal ethical and social values. This aspect made dioramas one of the most successful ideological tools of natural history during the modern era.[19]

Dion draws on the format of the diorama in many of his works, including Roundup. The final installation that resulted from Dion’s performance is separated from visitors by a clear zone of demarcation. The original installation conceived for the Ecologies exhibition featured a larger platform that included two worktables and a storage cabinet replete with the tools suitable for an entomologist: a microscope, petri dishes, a can of compressed air, specimen jars and test tubes, rubbing alcohol, Ziploc storage bags, a butterfly net, screwdrivers and tweezers, pencils and pens, brushes and droppers, and a collection of books on mites, millipedes, beetles (fig. 8). In this way, Roundup adapts eighteenth- and nineteenth-century naturalist modes of representation to turn the gaze back on the naturalist. The subject of this diorama is the habitat and behavior of the scientist studying the natural world.

Fig. 8. Mark Dion, Roundup: An Entomological Endeavor for the Smart Museum of Art, 2000, installation views, Smart Museum of Art, The University of Chicago. Photo reproduced in Smith, Ecologies.

Although the final version of the installation abbreviates the reference to the diorama, this sense of inversion is maintained by the inclusion of a mannequin wearing a naturalist’s costume, who, as mentioned, stands in for the artist himself. As the art historian Miwon Kwon has noted, “Dion is put on display, not as a theatrical actor in an artificial guise but as himself a specimen.”[20] In other words, Dion himself occupies the space of a taxidermy animal, himself a specimen for our visual consumption.

Dion’s focus on natural history derives from his “passion for interacting with nature, and a great passion for its forms of representation, whether that be the natural history museum, television, or the apparatus of collection.”[21] His work applies the methodology of institutional critique to the subject of natural history.[22] In his exhibition Natural History and Other Fictions (1997), Dion defined natural history as something that simultaneously addresses the history of nature and the human; a history of humans that has somehow been naturalized. He believes that history itself operates as something rather unnatural, as constructed by the very human whose story it seeks to tell.[23]

Fig. 9. Mark Dion, Landfill, 1999-2000, mixed media. Museum of Contemporary Art San Diego. Photo by Pablo Mason. © Mark Dion

Mark Dion’s landmark full-scale diorama titled Landfill (1999) was created a year before Roundup. It presents a life-size showcase of gulls and other animals feeding on a garbage dump (fig. 9). Like Roundup, Landfill also engages in relative visibilities that gesture towards a critique of realism. To deliver multiple layers of ideological values, Dion incorporates all the aesthetic elements of classical natural history dioramas: the perspectival painted background, taxidermy seagulls, and a foreground of scattered trash. What Giovanni Aloi has called “the non-human networks and ecosystems that we are substantially enmeshed in but that we culturally disavow” are placed front and center.[24] Humans are absent yet everywhere present in the accumulation of rubbish, and one can easily interpret the piece as a condemnation of humans’ disregard for the negative impacts of their actions upon the environment. Yet at the same time, the presence of seagulls also reveals the ability of some animals to adapt to and even thrive in anthropogenic environments. Although the type of ecosystem that we see in Landfill is not usually presented in museums of natural history, it is perhaps more representative of modern “nature” than the pristine, imagined landscapes of conventional dioramas.

In this sense, Dion challenges the contemporary natural history museum’s failure to acknowledge the entanglement of the human and natural world. As the scientist and art historian Giovanni Aloi has argued, landfills can be regarded as sites of anthropogenic truths.[25] Instead of understanding them as pure waste or pollution, we can instead view them as ecological biosystems that reveal the interconnectedness of human and non-human life. Another similar diorama by Dion is Paris Streetscape (2017, fig. 10), developed especially for the landmark exhibition titled Dioramas (2017) at the Palais de Tokyo in Paris. In a large-format glass showcase, Dion presented a section of the Paris cityscape. Although the garbage, plastic waste, and scrap metal initially seems to have nothing to do with nature, Dion’s diorama is nonetheless populated by urban animals, asking viewers to revise their assumptions about the relationship of nature and culture.[26]

Fig. 10. Mark Dion, Paris Streetscape, 2017. Courtesy Mark Dion / Galerie in Situ – Fabienne Leclerc, Paris. Photo: Aurélien Mole.

The same exhibition included the series Dioramas (1976-2016) by the Japanese photography Hiroshi Sugimoto, whose work is also on view for this exhibition at the Smart Museum. For this series, Sugimoto photographed the dioramas on display in natural history museums (especially the American Museum of Natural History in New York) but removed all the didactic and framing materials, allowing his photographs to seem, at first, like wildlife photographs. Also playing with illusionism, the Chinese artist Xu Bing has also used motifs of the diorama in his artistic creation. Inspired by traditional Chinese paintings, Xu’s ongoing diorama series Background Story (2004-2020) also challenges the viewers’ perception and questions the artificiality and realness of our surroundings (fig. 11). He uses natural materials like corn husks, crumpled paper, dried plants, and garbage and puts them against the frosted glass in a large-scaled lightbox. Viewed through backlit frosted glass, the arrangement resembles a delicately painted landscape, while the opposite side reveals the composition of both unnatural garbage and natural debris. As the products of contemporary art, all these installations address questions of staged vision by questioning and dissolving the illusion of a reconstructed reality.

Fig. 11. A front view of Background Story: Ten Thousand Li of Mountains and Rivers; Bottom: a back view of the same work exhibited in Vancouver, Canada, 2014. © Xu Bing Studio.

With a growing interest in the paradigms of natural history, contemporary artists like Dion, Sugimoto, and Xu, adapt the formats of the natural history museum to explore longstanding relationships between “nature” and “culture.” By engaging with the diorama format and the practices of collecting, classifying, and arranging upon which it is based, Dion questions and undermines the very nature of culturally constructed categories. Ultimately, his critique is concerned with the very categorization of knowledge itself. Dion’s artworks offer us a vast mirror reflecting our own participation in the construction and destruction of the so-called natural world, asking us to reflect on our place within the culture of nature and the nature of culture.

—

[1] Charles Baudelaire, The Painter of Modern Life: and other essays, trans. Jonathan Mayne (London: Phaidon, 1964), 43.

[2] Jakob von Uexküll, A Foray into the Worlds for Animals and Human: With a Theory of Meaning (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 142.

[3] Baudelaire, 33. “The life of our city is rich in poetic and marvelous subjects. We are enveloped and steeped as though in an atmosphere of the marvelous, but we do not notice it.”

[4] Andrew Yang, “Letting the City Bug You. The Artistic and Ecological Virtues of Urban Insect Collecting,” in City Creatures: Animal Encounters in the Chicago Wilderness, ed. Gavin Van Horn and Dave Aftandilian (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015), 218.

[5] Uexküll, 139.

[6] Ibid, 153.

[7] Yang, 216.

[8] Stephanie Smith, Ecologies: Mark Dion, Peter Fend, Dan Peterman (Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, 2001), 35.

[9] Volunteers include Candida Alvarez, Ramon Alvarez-Smikle, the American photographer Dawoud Bey, Patrick Engelking, Kris Ercums, the scholar, critic, theorist and editor of Critical Inquiry W.J.T. Mitchell, Axel Peterman, the artist Dan Peterman, Sander Peterman, Amy Rogaliner, the curator of the exhibition Stephanie Smith, and Hillary Weidemann.

[10] Mark Dion, “Artist’s Statement,” in Ecologies: Mark Dion, Peter Fend, Dan Peterman (Chicago: David and Alfred Smart Museum of Art, 2001), 37.

[11] Alissa Walls Mazow, Plantae, Animalia, Fungi: Transformations of Natural History in Contemporary American Art (Pennsylvania: Pennsylvania State University Press, 2009), 165.

[12] Smith, 41.

[13] Ibid., 41-42.

[14] Ibid, 169.

[15] Richard Meyer, “Warhol’s Clones,” Yale Journal of Criticism 7, no. 1 (spring 1994): 79-109.

[16] Mazow, 155.

[17] University of Illinois Extension, “Let’s Talk about Insects”: http://urbanext.illinois.edu/insects/01.html

[18] Giovanni Aloi, “Dioramas: Power, Realism, and Decorum,” in Speculative Taxidermy: Natural History, Animal Surfaces, and Art in the Anthropocene (New York: Columbia University Press, 2018), 103.

[19] Ibid, 104.

[20] Miwon Kwon, “Unnatural Tendencies: Scientific Guises of Mark Dion,” in Natural History and Other Fictions: An Exhibition by Mark Dion (Birmingham: Ikon Gallery, 1997), 41.

[21] Mark Dion and Alex Coles, Mark Dion: Archaeology (London: Black Dog Publishing, 1999): 47.

[22] Ibid, 49.

[23] Mark Dion, Natural History and Other Fictions: An Exhibition by Mark Dion (Birmingham: Ikon Gallery, 1997), 53-77. This exhibition appeared in the Ikon Gallery, Birmingham, January 25-March 21, 1997; Kunstverein, Hamburg, June 19-August 10, 1997; De Appel Foundation, Amsterdam, August 29-October 19, 1997.

[24] Aloi, 105.

[25] Ibid, 106.

[26] Richard Kalina, “Scene Stealers: ‘Dioramas’ Set Many Stages at the Palais de Tokyo,” ARTnews, August 17, 2017. https://www.artnews.com/art-news/reviews/scene-stealers-dioramas-set-many-stages-at-the-palais-de-tokyo-8832/

—

This site is for educational purposes only. Certain images on this website are protected by copyright and may be subject to other third party rights; downloading for commercial use is prohibited.